CNBC report notes how Jones Act leads to higher Matson shipping prices

Higher prices for smaller U.S.-built ships is a losing combination for captive consumers in Hawaii and throughout the nation

from Grassroot Institute

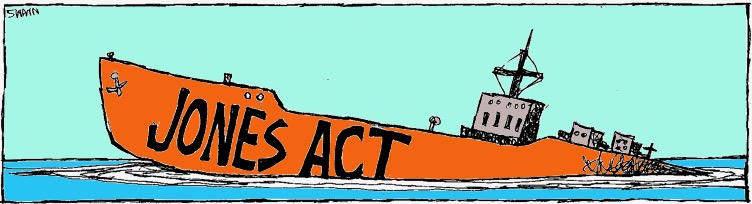

CNBC's "Money Report" featured an analysis yesterday that described well the bind that the federal maritime law known as the Jones Act has created for customers of U.S. shipping companies such as Matson of Hawaii.

The Jones Act, aka Section 27 of the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, was intended to protect U.S. shipbuilders and waterborne transport companies by limiting shipping between U.S. ports to only vessels that are U.S. flagged and built and mostly owned and crewed by Americans.

But this law hasn't come without a significant cost to consumers in Hawaii and throughout the nation, especially since U.S.-built ships often cost at least four times more than high-quality foreign-built vessels.

As noted by reporter Lori Ann LaRocco in her article "Biden promise to rival China on shipbuilding faces a big economic problem":

"In November 2022, Matson … ordered three vessels from the Philly Shipyard with a carrying capacity of 3,600 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs). The cost for each was reported at $330 million."

Meanwhile, "According to Darron Wadey, an analyst at shipping consultant Dynamar, CMA CGM ordered 16 vessels from China's COSCO and OOCL at the same approximate time, vessels with a carrying capacity of 24,000 TEUs, and a cost between $240 million-$250 million each. 'So not only were these vessels $80-$90 million cheaper than the Matson units, but they were six to seven times bigger,' Wadey said."

Also according to Wadey: "In 2023, Matson's revenue divided by containers carried worked out to around $3,000 per TEU. For global operator Hapag-Lloyd, with access to cheaper tonnage and operating worldwide, the revenue per TEU was $1,600."

In other words, the economics of vessels with higher build prices and less carrying capacity don't add up. To make the vessels commercially viable, Wadey said, ocean carriers need competitive return on investment metrics tied to container freight rates.

"In effect," LaRocco wrote, "Hapag-Lloyd can charge less and still make money, while the smaller U.S.-made [Matson] vessel has to charge higher freight rates to generate a profit."

A 2020 report commissioned by the Grassroot Institute of Hawaii estimated that the Jones Act premium costs Hawaii consumers about $1.2 billion a year, or almost $1,800 per average family, with side effects including thousands of lost jobs and lower tax revenues for our state and local governments.

Can we please just go ahead and update the Jones Act for the 21st century?