Economic Perspective of Maui’s Devastating Wildfires

by James Mak, Paul Brewbaker, and Frank Haas, UHERO, Sept 8, 2023

Lahaina is a very special place with so much deep, rich history. Over time, it’s evolved. It’s been many things. It’s been the capital of the Hawaiian Kingdom. It’s been home base for generations of Maui chiefs. It’s been a center of commerce in whaling. It’s been a center of commerce in sugar. And, more recently, it’s been a center of commerce in tourism… Lahaina is important to the visitor industry, but first and foremost, as the home of so many residents.

Ilihia Gionson--Hawaii Tourism Authority, 2023.

The inferno that destroyed Lahaina on August 8 caused at least 115 fatalities, each a tragedy in itself.

Our hearts join with those across Hawaii and the world in mourning as we process this horrific loss.

Introduction

On August 8, 2023, swift moving wildfires fueled by dry grass and spread by strong winds from a passing hurricane wiped out almost the entire seaside town of Lahaina in West Maui. (The population of Lahaina CDP was 12,702 in the 2020 census.) Before the disaster, Lahaina was a vibrant tourist town that, according to Fodor’s Maui travel guide (2023), “houses some of Hawaii’s best restaurants, boutiques, cafes and galleries.” Now, it’s gone. Tragically, the deadliest wildfires in more than a century in the U.S. killed at least 115. Over 2,200 buildings (mostly residential) were reduced to rubble and another 500 were damaged resulting in nearly $6 billion in property losses. Many residents fortunate enough to escape the raging fires are in dire need of just about everything—food, clothing, shelter, water, and jobs.

As of August 31, the State of Hawaii Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism (DBEDT) listed 834 businesses in the disaster area that were closed. Their aggregate pre-disaster annual sales totaled nearly $900 million with $500 million of that coming from tourism-intensive sectors.1 Two historic hotels—the Plantation Inn (18 rooms) and the Best Western Pioneer Inn (34 rooms) were burned to the ground. In total, 16 visitor properties with 474 rooms were lost representing about 2% of the total island visitor plant inventory. Most of the units lost were in two condominium hotels (326 rooms). Lahaina was a place where visitors went to play and not so much a place where they stayed.

Further up the coast (and still in West Maui), visitor accommodations in Kaanapali (4.1 highway miles away) and Kapalua (another 6.4 miles) survived the inferno. Hotels, short term vacation rentals, timeshares and other visitor accommodations in the rest of Maui—which comprise nearly half the island’s visitor plant inventory—remain unscathed. In response to the disaster, visitors have heeded the call to leave West Maui to facilitate disaster relief efforts. Hoteliers and owners of vacation rentals in West Maui are using freed-up rooms to temporarily house emergency workers, displaced residents, and their own employees.

As a result of the wildfires, Maui faces a sea of economic, social and political challenges. The University of Hawaii Economic Research Organization (UHERO) has released a report on many of these complex issues. In this essay, we provide an economic perspective on the Maui wildfires, specifically on rebuilding Lahaina and restoring Maui Island’s (and, indeed, the state’s) overall (macro-) economy. Rebuilding Lahaina and restoring the economy are essential to generate the resources to fund recovery.

Drawing Lessons from Hurricane Iniki in Kauai, September 1992

Many Hawaii residents still remember Hurricane Iniki, a Category 4 storm which passed directly over Kauai (Population about 54,000) on September 11, 1992 with winds up to 160 mph. Examining Kauai’s experience can provide valuable insights for Maui.

Iniki claimed several lives and injured about 100. The Hawaii Emergency Management Agency estimated the property damage at $3 billion, or more than $6 billion in 2022 prices. The Federal Emergency Management Agency reported that about one-fifth of Kauai’s 20,000 homes were destroyed or badly damaged, and most hotels and government buildings also suffered damage.

Kauai’s tourist industry, which directly and indirectly accounted for about a third of the county’s economic output, took a significant hit. The executive director of the Kauai Visitors Bureau recalled that “Tourism…dropped off the edge of the Earth.” On an annualized basis, total visitor days on Kauai plummeted by more than 50% from 6.468 million visitor days before the hurricane in 1991 to 3.013 million visitor days in 1993. It wasn’t until 1998 that total visitor days finally surpassed the 1991 count. At the start of 1992 Kauai had 7,778 lodging units; after Hurricane Iniki swept through Kauai, the number of lodging units in the county fell by 40% to 4,631 in the following year. Visitor plant inventory on Kauai did not surpass the 1992 room count until 2004.

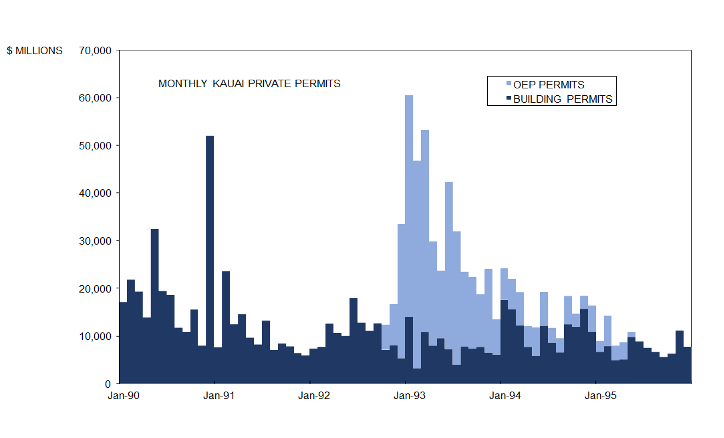

Kauai County’s effort to expedite rebuilding after Iniki shows what can be achieved with imagination and determination. Right after September 11, the County established the Office of Emergency Permitting (OEP). OEP was a pop-up building permit agency designed specifically to facilitate reconstruction. OEP’s creation was an important institutional step forward, segregating process for recovery from the ordinary processes of daily governing. Permit issuance began immediately and the following figure (data from Paul Brewbaker’s personal files) shows a four-month acceleration in building permits (in nominal dollars) to reach its peak during the first quarter of 1993.

While Kauai’s civilian unemployment rate more than tripled from 4.1% in 1991 to 13.0% in 1993, (more than three times the state average), the Washington Post reported (January 29, 1993) that “A frenzy of construction activity is evident throughout the island…”

Arguably, the most important lesson from Iniki is that it may take many years to recover from a natural disaster. Kauai County leaders opined that it took about a decade for the island to completely recover from Iniki. The iconic Coco Palms Resort was never restored.

Rebuilding Lahaina and Restoring the Economy

The scale of the destruction in Lahaina suggests that it will be a daunting task to rebuild. Moody’s RMS estimates that insured property losses in Lahaina and Kula range between $2.5 billion to $4 billion. Total economic losses—which include “property damage, contents, and business interruption, across residential, commercial, industry, automobile, and infrastructural assets—range between $4 billion to $6 billion, of which 75% of the losses is covered by insurance. Rebuilding Lahaina will necessitate significant government involvement at the federal, state and county level because they can marshal the resources necessary to do the job.

Even before rebuilding, debris from the disaster must be cleared and disposed of. On an island where space is limited, how to dispose of debris is important. Iniki’s debris largely wasn’t burned debris; hence, recycling was an option to the expedience of landfilling. Kauai officials concluded that “It pays to adhere to long range plans. Quick solutions will be attractive, but in the long run they may produce very costly problems…” Managing disaster debris on Maui is more complicated. On Maui, burned material leaves toxic ash and dust that can be harmful to humans for years unless properly treated and disposed. Air and water contamination (should the fires be followed by a storm or heavy rain) could trigger another disaster after the initial fire.

Lahaina won’t be rebuilt as an exact replica of the pre-disaster town. Nor should it be. The goal should be to build back better, using improved building materials and technologies and taking into consideration the anticipated effects of climate change and long run demographic and economic trends.

There are also legal considerations. According to David Callies, Professor of Law Emeritus at the University of Hawaii law school and an expert on Hawaii land use regulations, “So long as Lahaina remains in the state urban land use classification, Maui County zoning, plans and subdivision code govern/apply.”2 He surmises that new required setbacks from the ocean are considerable and might “not permit much of the rebuilding on Front Street.” Moreover, “as much of Lahaina previously consisted of lots of nonconforming uses grandfathered in but could not likely be rebuilt as a matter of right” unless the State were to create a redevelopment district (like Kakaako, Oahu) covering Lahaina that would supersede all Maui county land use and planning controls except building codes.

Callies goes on to say that private landowners will have the same property rights they had before the disaster, “with the caveat that use restrictions, some in place before, and some likely new ones, imposed under government’s police power, are likely to make rebuilding on existing, nonconforming lots difficult if not impossible, so this a loss of some preexisting property rights which are probably not compensable. Of course, if government actually physically invades or takes private land, it cannot do so without paying the owner just compensation.”3

Some community activists in Maui don’t want to hear from the governor that he has a plan to rebuild Lahaina; they want full resident participation in the decision-making process. This may be driven in part by fear that locals will be pushed/priced out of a redeveloped Lahaina. It’s not an unfounded fear as new construction will be more expensive than what was there before. In a live-streamed speech to residents on all the islands on August 18, Governor Green said, “Lahaina belongs to its people—and we are committed to rebuilding and restoring it the way they want it.”

One thing that we have learned from tourism planning in Hawaii is that Hawaii is very good at crafting plans that involve broad community input. The problem has been ineffective implementation due to poor governance. Effective governance requires vertical coordination (coordination between federal, state and county governments), horizontal coordination (inter-departmental/agency coordination within a government) and involvement of community stakeholders. This would require establishing an engagement mechanism to facilitate coordination. And adequate funding is essential.

The second challenge, the recovery of the Maui (and the state’s) macroeconomy is, currently, overshadowed by the immediate priority to find the missing and manage disaster relief. Among Hawaii’s four counties, Maui is the most dependent on tourism. DBEDT estimates that visitor spending in Maui accounts for 35.2% of the county’s GDP; another 2.6% of Maui’s GDP is attributable to visitor spending in the other three counties, a small amount of that making its way to Maui businesses.4 Together (and including all the multiplier effects), visitor spending in Hawaii accounts for 37.8% of Maui’s GDP. Similarly, visitor spending accounts for 40.3% of Maui County’s jobs. Thus, bringing tourists back would be the most logical economic recovery strategy.

Very early estimates of foregone tourism receipts due to reduced tourist travel to Maui range between $200 million and $300 million for the period August 9 to August 31. For the state, one county’s loss is another county’s gain, as many tourists who otherwise would have gone to Maui have elected to go to Hawaii’s other islands. STR data show that hotel occupancy in the other islands—especially Oahu—has risen and is primarily due to the Maui wildfires.

All things considered, a doom and gloom scenario blamed on the wildfires may be too stark. On the plus side of the accounting ledger is government disaster aid money coming in to offset some of the losses. There is also private aid that’s pouring into Maui. Like Kauai, the expected surge in post-disaster construction spending will provide a big boost to the economy. Whether or not all of that will be enough to bring the economy back won’t be known until much later. It is noteworthy that while Iniki inflicted billions of dollars of property (i.e. capital) loss in Kauai, total inflation-adjusted personal income in Kauai County did not decline in the immediate years after the hurricane. Kauai’s resident population and labor force were higher in 1993 and 1994 than in 1991 though civilian employment fell. The encouraging news on tourism is that Maui’s lodging sector, the bedrock of the visitor industry, has kept its physical capital stock largely intact.

To bring tourism back, there is also need for workers and workers need housing. After the wildfires, housing is a pressing need in Lahaina. Shannon Van Zandt, Professor of Urban Planning at Texas A&M University, who studies housing recovery after disasters, argues that rebuilding stable, long-term housing must proceed in tandem with rebuilding businesses since workers need housing to return to work and businesses need workers to operate.

Van Zandt advocates for community land trusts (CLT) as a way to create affordable housing post-disasters. A CLT is a non-profit organization that develops affordable leasehold housing. The private trust owns the land and leases it to a homeowner on a long term (e.g. 99-year) renewable ground lease; if the home is sold in the future, it has to be at a restricted price to keep it affordable in perpetuity. Currently, there are 38 states with over 250 CLTs in operation. There is also one on Maui—Na Hale O Maui. To date it has sold 46 single family homes. Obviously, CLTs alone can’t meet the post-disaster demand for affordable housing on Maui. A multi-pronged approach is necessary.

In June of this year, Governor Green signed several bills into law that would significantly increase access to affordable housing—both rental and ownership—to qualified Hawaii residents. (U.S. Census Bureau data show a slightly larger percentage of Lahaina households rent (50.3%) than own their homes; the opposite is true for the county as a whole.) Although the Acts were not specifically intended to benefit victims of wildfires in Lahaina, they do (or can be modified to) apply to disaster victims.

There is another piece of good news from Maui: the wildfires are burning down traditional local construction industry resistance to modular and prefabricated homes which can provide quick and cost-effective houses to those displaced by the fires.

After some initial confusion and mixed messaging whether visitors are welcome or not welcome on Maui, the current economic recovery strategy is to encourage visitors to return with the specific exception of West Maui. State and county officials are sending out a coordinated message to the travel trade that the rest of Maui is open for business. (Many in Maui are not happy with the decision arguing that more time is needed for residents to grieve.) Potential visitors who may not be familiar with Hawaii’s geography are also being informed that the rest of Hawaii welcomes them. An initial $2.6M tourism recovery campaign to run through October was approved by the Hawaii Tourism Authority. While the welcome mats are out, visitors are advised to behave responsibly in the Aloha State. Thus, there is hope that tourism’s recovery on Maui from the wildfires that devasted one part of the island (about 2,170 acres or 3.39 square miles were burned) will be faster than Kauai’s recovery from Hurricane Iniki that devasted almost the entire island.

Maui’s most popular tourist attractions are its parks and natural attractions (e.g. Haleakala volcano). Hawaii Island and Kauai also have their natural attractions, but they don’t have a Lahaina. Lahaina’s unique mix of oceanfront dining, galleries, shopping, and history (monarchy, whaling, and missionaries) contributed to Maui’s distinctiveness. The real test of Lahaina’s importance to tourism on Maui is whether or not tourists will find the island to be as attractive a destination without Lahaina as it existed before the fires.

Final Observation

Visitor industry’s recovery from the wildfires may not be welcomed by many Maui residents who favor a more diversified economy and a limit placed on the number of visitors relative to the size of the resident population. Policy 4e.2.3.a of the Maui Island Plan 2030 aims to “Promote a desirable island population by striving to not exceed an island-wide visitor population of roughly 33 percent of the resident population” As of May 2022, Maui Island’s resident population was about 155,000 while the average daily visitor census was 64,000, or 41% of the resident population. This demonstrates how difficult it is for the government of a small open economy like Maui to control the inflow of tourists. It will be interesting to see if the economic fallout from the wildfires will change Maui residents’ attitudes—either more favorably or less favorably—toward tourism.

Footnotes

[1] DBEDT, Research and Economic Analysis Division, Maui County Economic Conditions, August 31, 2023. The tourism intensive sectors are: (1) retail trade, (2) transportation and warehousing, (3) arts, entertainment and recreation, and (4) accommodation and food services.

[2] Email from David Callies to James Mak dated August 21, 2023.

[3] Email from David Callies to James Mak dated September 2, 2023.

[4] The estimates include direct, indirect and induced effects of visitor spending. Kauai is barely behind Maui. Directly and indirectly (i.e. leaving out the induced effects) tourism’s economic contribution to Maui as a percent of the county GDP is 29.3% (Estimates provided by Eugene Tian to James Mak and Paul Brewbaker by email on September 1, 2023.)