Embracing TOU: Nudges, Rates, and Renewable Energy

by Michael Roberts, Nori Tarui and Ethan Hartely, UHERO, August 21, 2023

Hawaiian Electric Company is about to embark on a significant experiment: a pilot program introducing time-of-use (TOU) pricing. Designed to reduce electricity prices during daylight hours when solar power is abundant and increase them during the evening when the sun sets and demand rises, this initiative could reshape how 17,000 customers consume energy. If you’re among the chosen, you’ll be automatically enrolled unless you opt out.

The Power of Nudges

This enrollment method leans on insights from behavioral economics, particularly the power of nudges. This subfield of economics—merging psychology and economic principles—reveals our propensity to stick with default options. Consider 401K enrollments: many employees won’t opt-in even with lucrative matching offers. However, change the system to auto-enroll with an opt-out provision and participation skyrockets.

Richard Thaler, a Nobel laureate, and Cass Sunstein wrote the best-seller Nudge, which popularized this concept. These ideas were so influential that the Obama administration created a special unit to incorporate such nudges into public policies.

Nudges, however, are double-edged. They can guide us towards beneficial choices, but they can also exploit inattentiveness. Setting a default that isn’t in a person’s interest risks backlash and mistrust. This ethical consideration is paramount, especially in public policy.

Breaking Down TOU Rates:

For Oahu residential customers

- Daytime (9 am-5 pm) – 19 cents/kWh (Thanks to abundant future solar power!)

- Evening (5 pm-9 pm) – 57 cents/kWh (Demand peaks as the sun sets)

- Night (9 pm-9 am) – 38 cents/kWh

For comparison, the standard rate is 36.7 to 40.2 cents per kWh and does not vary by time of day.

While rates differ across islands and customer classes, all TOU rates will be similar, with evening rates thrice daytime rates and nighttime rates twice daytime rates.

What Does TOU Mean for You?

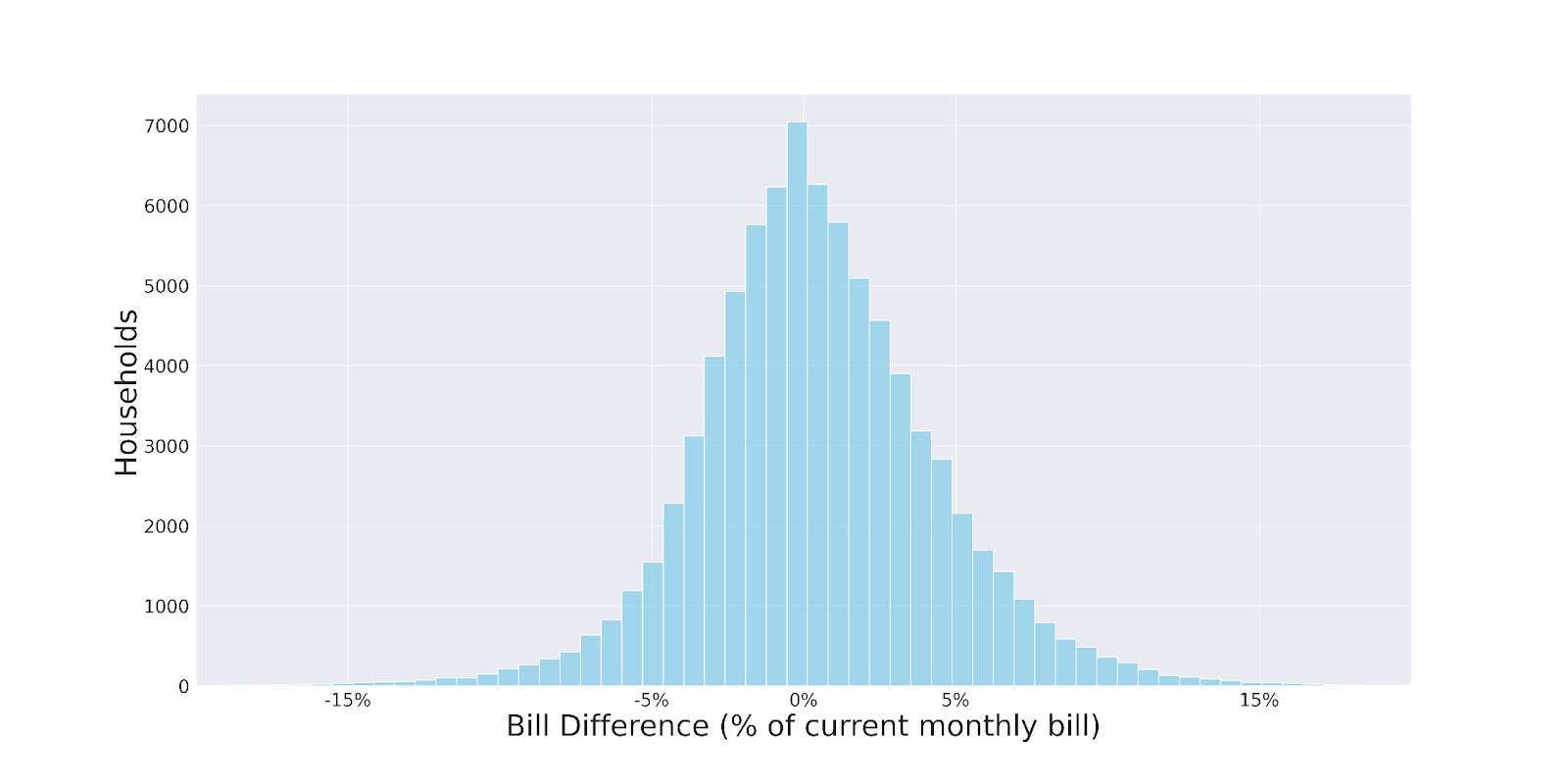

If You Don’t Have Rooftop Solar:

Your bill might not change much. The graph below shows estimated bill impacts if customers make no adjustments in electricity use.1 But, making some simple adjustments should allow most customers to save. If you have an electric water heater, set the timer so it only runs during the daytime, and increase the thermostat slightly. Also, try washing clothes and using dishwashers during the day.

Estimated change in bills for customers without rooftop solar

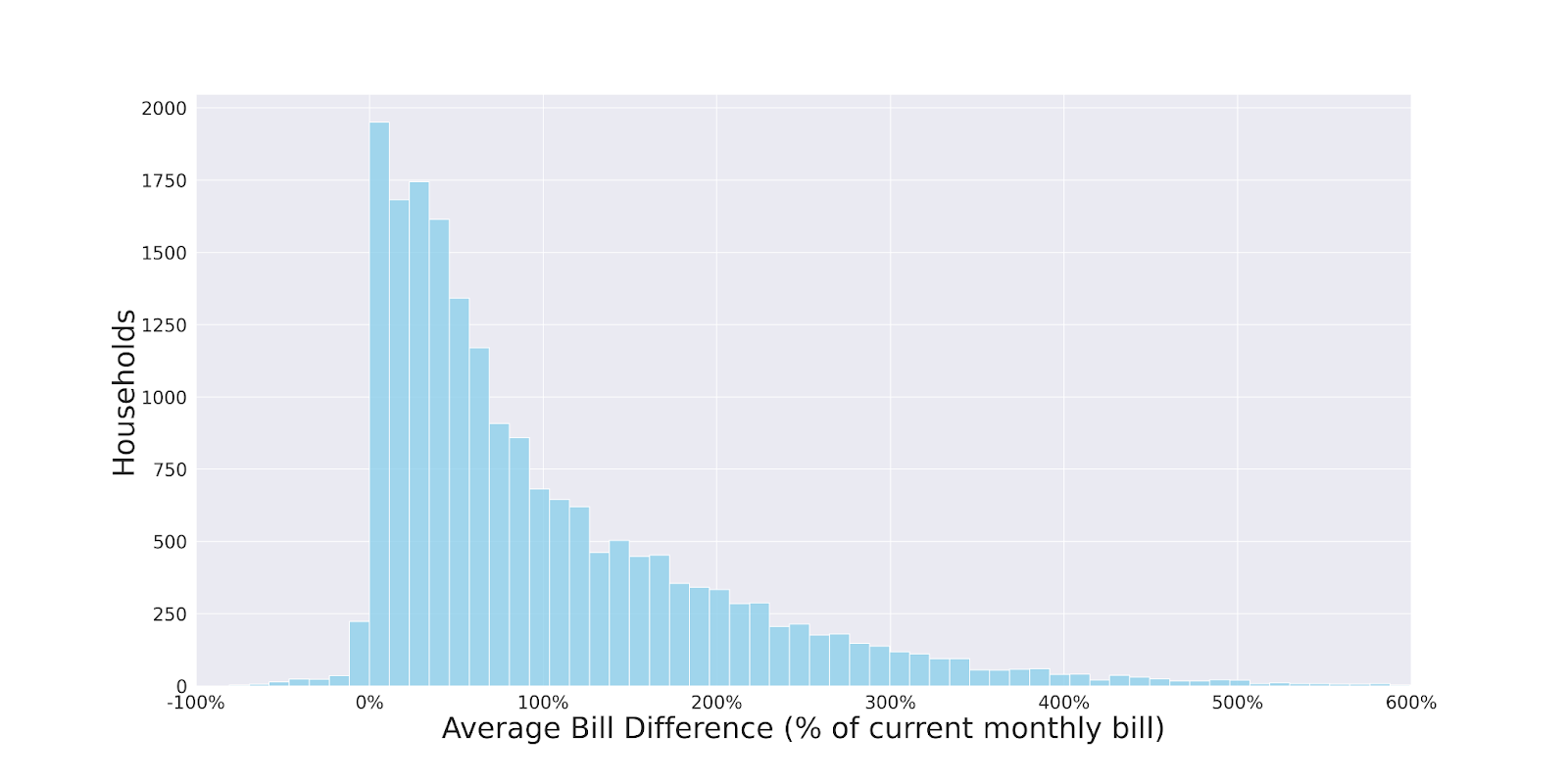

If You Have Rooftop Solar:

You’ll likely see a big increase in your monthly bill, especially if you don’t have a battery. For those grandfathered on a NEM,2 your credit for back-feeding energy to the grid during the daytime will be about half what it is currently, and you will pay much more during the evening and night. You’re unlikely to be able to shift enough to save, especially if you can just keep paying the minimum possible bill by opting out of the TOU program.

Those on other rooftop solar programs (CGS, CGS+, etc.)3 are also likely to lose, but the amounts are smaller, and some might be able to save by shifting. Hawaiian Electric will offer a rate comparison tool to help you decide.

Estimated bill changes for solar customers with NEM+, CGS, CGS+, CSS & SE

Estimated bill changes for solar customers on NEM

Thankfully, there are a few guardrails built into the rollout that prevent customers’ bills from increasing too much during the initial months of the pilot, which should give them extra time to opt-out.4

A Missed Opportunity

Rooftop solar customers, especially NEM customers without batteries, have the most potential for shifting demand. So it is a shame they cannot gain from participating in the TOU program. These customers are likelier to own electric vehicles and could charge them during the day instead of the evening and night. They also might be enticed to install a battery for backup purposes anyway.

Some challenges with making TOU work for solar customers stem from more profound problems with rate design that we return to below.

Ethical Concerns

While nudges can be effective, pushing NEM customers towards an option that is very unlikely to be in their best interest may raise ethical eyebrows. Worse, it will sew distrust of variable pricing programs that we need to make clean energy as cost-effective as possible. Note that a disproportionately large share of the customers selected for the TOU pilot has rooftop solar, most of which are NEM.5

Rate Design and Fairness

Stepping back, challenges with the TOU program stem partly from other problems. Specifically, customers installing rooftop solar receive tax credits and cross-subsidies from other customers implicit in tariff design. The tax credits are perfectly reasonable, given our climate crisis. But the cross-subsidies are unfair and encourage too much self-generation, especially if grid-scale alternatives can be more cost-effective.6

While the State has ended new NEM enrollments, reduced the back-feeding credit for new rooftop solar customers, and incentivized battery installation, new rooftop solar installations continue to receive large cross-subsidies from other customers. This cross-subsidy happens whenever a customer’s bill savings from their solar installation exceeds Hawaiian Electric Company’s avoided costs.

At this writing, Hawaiian Electric’s avoided cost per kilowatt-hour is 17.8 cents during both peak and off-peak hours, which is less than half the standard incremental charge of 36.7 to 40.2 cents per kWh.7 Thus, well over half a rooftop solar customer’s bill savings represents a cross-subsidy from other customers. The cross-subsidy appears on bills as the “RBA adjustment” and eventually gets folded into other parts of the bill.

So, rooftop solar customers should pay more. But the extra cost should be transparent and apply to all, not just those too inattentive to opt out of the TOU pilot.

A Way Forward

A simple solution is to adjust per-kWh rates to reflect avoided costs in the first place. For example, an initiative in California would reduce per-kWh charges, increase the fixed monthly customer charge (presently just $13.48 per month on Oahu), and make the fixed charge progressive—have wealthy households pay more than lower-income households. The fixed charge would be progressive regardless of whether customers have rooftop solar.

These adjustments would increase efficiency and fairness while eliminating cross-subsidies. At the same time, a more significant fixed charge would give rooftop solar customers something above the minimum bill that they could offset by shifting demand per TOU rates.8 Many more would be able to benefit from participating.

We must proceed with care. Today, electricity costs do not vary by time of day on Oahu, even if they will in the future. Eventually, variable pricing should be part of the equation, for if implemented well, it can reduce the cost of clean energy and provide significant social benefits. UHERO provided some guidance about how to do this in 2015. At the same time, new solar PV is cheaper and greener than Hawaiian Electric’s oil-fired power. So, it should be possible to accelerate our transition to clean energy while lowering customers’ bills. Getting rate design right would allow these benefits to be shared broadly across stakeholders and customer classes.

---30---

Footnotes

1 Our characterization of the bill impacts from TOU are based on our reading of the PUC’s decision, existing tariffs, and correspondence with Carl Freedman, a consultant for the PUC, who shares the same understanding that we do. But he provided a disclaimer: “As with the NEM program when it was originally implemented, some of the fine details regarding billing for NEM were only firmly realized when […] the billing format and calculations were developed. At this point I have not seen an example NEM bill complete with underlying calculations.” We acknowledge that Hawaiian Electric Company shared with us anonymized advanced metering infrastructure (AMI) data. We constructed simulated bills using the AMI data. We only have AMI data from October 2022 through March 2023, and there are strong seasonal patterns in both renewable energy supply and electricity demand, and we made some adjustments to account for this which may be imperfect. Any errors in our interpretation of the statutes and estimated bills are ours and not the responsibility of the PUC, Hawaiian Electric, or anyone we consulted.

2 NEM stands for “net energy metering” which charges customers with rooftop solar just like regular customers, but on net-use.

3 CGS stands for “customer grid supply” and provides a credit of 15.07 cents per kWh for backfeeding while CGS+ provides a credit of 10.08 cents per kWh.

4 Specifically, for the first six months of the pilot program, residential customers will be protected from an unexpected surge in their bill. There is a 6-month cap that will keep their bill from going up more than $10 a month compared to what would have been charged on the pre-pilot rate for the same month. Commercial customer bills will be capped at no more than a 4% increase compared to what would have been charged on the existing rate for the same month. While these safeguards allow extra time to opt out, many customers may overlook the small increases, especially if they pay their bills automatically.

5 We understand that NEM and solar customers were more likely to have advanced meters installed at the time the sample was selected in December 2022.

6 Distributed generation may be economical in Hawaii given our scarce land resources and unusually high cost of grid-scale alternatives.

7 If HECO’s costs do not vary by time of day, you might wonder what the point of TOU pricing is. Presumably, Hawaiian Electric and the Public Utilities Commission are thinking about how costs will change as more renewable energy comes online over the next few years. What they learn about customers’ ability to shift demand to different times of day could influence investment decisions along the path to 100% clean energy.

8 If the per-kWh rate equaled Hawaiian Electric’s avoided cost, there would be no need for a “minimum bill” or cap on the credit for back-feeding. Customers could get paid for supplying power to the grid, possibly saving land resources. Not only would this simplify rate design for all customers, it would encourage those with ample roofs to supply power to others, but only if it is cost-effective.