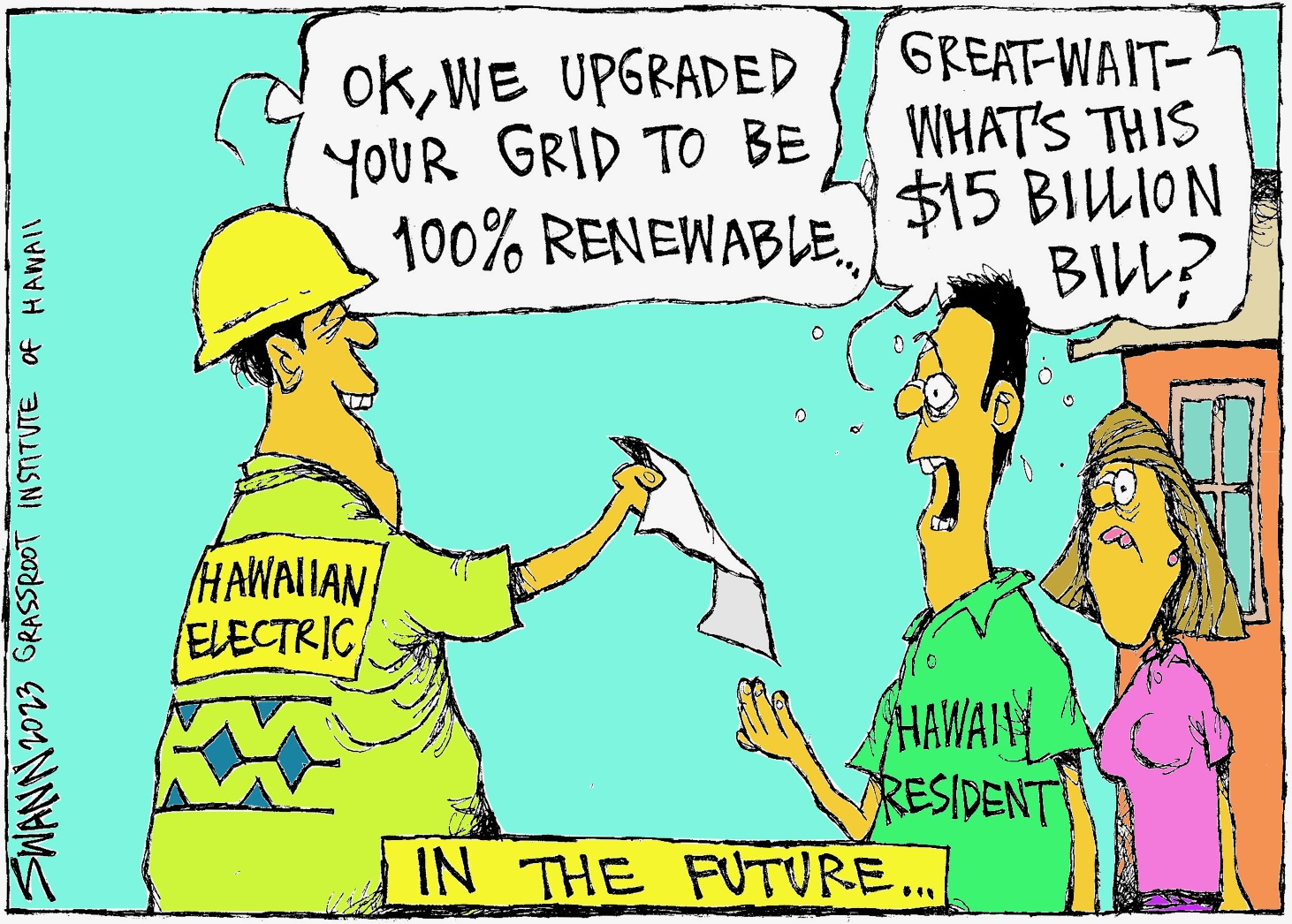

Can Hawaii residents afford 100% renewable energy?

from Grassroot Institute of Hawaii, July 11, 2023

Implementing 100% renewable energy in Hawaii is official state policy, but can Hawaii residents afford it?

That was the question posed by Joe Kent, executive vice president of the Grassroot Institute of Hawaii, in a conversation earlier this month with host Howard Wiig on the “ThinkTech Hawaii” program “Code Green.”

Wiig said implementing renewable energy is essential to mitigate the effects of climate change. He said it can pay for itself within just a few years, and can be very efficient.

Kent, however, said, “We see a lot of people who have trouble just paying for their own home bills — let alone paying for the state’s bills, … so, my interest in the climate change and renewable energy question is: What is the cost? You know, what is it actually gonna cost the average working family in Hawaii or a single person, in a state that already has the most expensive energy bills in the nation?”

For example, Kent said, Hawaiian Electric Co. recently released its integrated grid plan, which put the cost of interconnecting the state’s planned renewable energy plants at around $9 billion — and that doesn’t include the cost to build the plants themselves.

“The problem is, we don’t have those billions, and paying it back has to take into account the debt service costs,” he said.

Kent noted that many renewable energy ventures have involved taxpayer subsidies. He said when he toured renewable energy plants across the U.S. about a decade ago, there was always someone at each plant who would tell him the venture “can’t actually profit and make this sustainable without huge government subsidies.”

Subsidies, he said just “exports the costs, perhaps, to taxpayers. … So if we’re trying to save money, it doesn’t make sense to save money on the one hand, and then lose money on the other.”

Kent said other issues affecting the switch to renewable energy include growing environmental opposition to solar farms and windmills; the rush around the world to mine for more lithium; Oahu’s land constraints; and the fact that Hawaii is isolated from other states and cannot just switch to out-of-state suppliers when local energy production is down.

He also said much of the push for renewable energy is based on the assumption that oil prices will triple in the near future, but such predictions are frequently wrong.

TRANSCRIPT:

7-3-23 Joe Kent with host Howard Wiig on ThinkTech Hawaii

Howard Wiig: Good afternoon from beautiful Honolulu. This is Howard Wiig, “ThinkTech Hawaii” program “Code Green.” I have the honor of having as my guest today, executive vice president of the Grassroot Institute, Mr. Joe Kent. Welcome, Joe.

And what we’re gonna be talking about is the economics of dealing with climate change. And let me set this stage by saying that I’m in the field of energy efficiency and doing whatever we can to ameliorate the effects of climate change.

My attitude, and the attitude of my colleagues, is that while we have many, many problems in this world — Russia-Ukraine, so forth — the 800-pound gorilla overshadowing everything is climate change.

It is the tsunami that is going to wash over us pretty darn soon. We don’t know if it’s one year or five years, but it’s gonna come on like gangbusters. In fact, it already is coming on like gangbusters.

And when I think of the economics of that, I make the analogy of parents who discover that their young child has a very rare disease, and it’s life-threatening, and insurance is gonna cover most of the costs, not all of it, and over the next few years, they’re gonna have to pay out, from their pockets, $100,000 to keep this child alive.

Do they think cost-benefit? No. They just do it. And that’s a pretty extreme analogy for what I and many others think of when we need to deal with climate change.

Joe Kent: Oh, yes. Well, actually, I think it’s a great analogy, $100,000, because, you know, I was looking at the costs of Hawaii’s debts and unfunded liabilities and capital expenditures, deferred maintenance, energy, you know, renewable energy costs. And, if you rack up all of those costs, it’s over $100,000 per person.

And so, you know, that’s over $100 billion dollars. And so that is a huge cost and a lot of those initiatives, people feel passionately about each of them, you know, that we need to pay our debts, you know, obviously; we need to fund the public retirement systems; we need to make sure our bridges don’t fall.

And on top of that, there’s these energy goals, and so I think, actually, your analogy is perfect.

Wiig: And let me give you a real soft opening on this here. My own personal finances improved drastically when an economist friend of mine said, “Howard, pay off all your credit cards, settle all your debts except your mortgage.”

And I took his advice, I did it, and — boom! — instead of having to pay $200 here, $300 there for different credit card debts and other kinds of debts — boom! — that money just kept sitting in my bank and getting larger and larger and larger, because I was controlling my expenses. Is that a good analogy to lead you off with, Joe?

Kent: [chuckles] Yeah. I think it’s always good when we can try to think about our home budget in the same way that we think about Hawaii state budget, because, you know, the state has a “credit card,” so to speak. It can put debt on that card. And it can, you know, pay the interest payments and the debt service just like we pay a credit card bill.

And so, yeah, it’s always a good thing to think about, you know, how does a family budget look like and what does the state do? If the state were a family, would its finances actually be in order?

And so, of course, you know, I work at the Grassroot Institute of Hawaii, which takes a hard look at the numbers, and we’re very concerned about the financial sustainability of the state.

We see a lot of people who have trouble just paying for their own home bills — let alone paying for the state’s bills — and having such trouble that they’re leaving the state, which they’ve been doing now, on net, since 2016. You know, tens of thousands of people have left every year because of the cost of living.

And so, my interest in the climate change and renewable energy question is: What is the cost? You know, what is it actually gonna cost the average working family in Hawaii or a single person, in a state that already has the most expensive energy bills in the nation?

You know, so I’m just trying to map out the cost, and it turns out it’s kind of hard to find those costs because there’s a lot of complexities to it.

Wiig: Um-hmm. Well, let me throw into this the concept of payback time.

Whereas a lot of government costs say repairing a bridge, we do not want bridges falling down. We had that in Philadelphia. I don’t think we want to repeat Philadelphia’s experience. But how do you measure the payback time of that? Well, you don’t have accidents, but that’s way in the future.

But in terms of energy efficiency — my own field — if you spend a couple of extra dollars, say, just for instance, on more efficient lights in your home, or in government or streetlights, you’re going to be way, way up in your efficiency. And say you pay two extra dollars for the lamp, but you’re getting twice the efficiency, the payback time, those two extra dollars are going to be paid back within months, not years.

Kent: Oh, yes, yeah.

Wiig: That’s one way where we look at efficiency: How quick is the payback time?

Kent: That’s a great lens. You know, I always love it when renewable energies or clean energies cost less, because what we see when that happens is the market forces naturally gravitate towards adopting those technologies. So your example is perfect.

You know, my wife looks for the light bulbs that will cost us less money, and in so doing, we’re actually being more sustainable that way. And so, you know, in the same way, we want the economy to drive towards those energy technologies that are more efficient and more sustainable.

Wiig: And then I hear counters to that, “Well, solar energy is so expensive, so forth, so forth, and it’s going to have a 20-year payback.” And, incidentally, I, in doing my calculations and recommending things, I put a five-year payback as the absolute max, and generally, I’m getting under three-years payback, and in many cases, zero-time payback. You just adopt a different technology.

But some people claim, “Oh, solar energy is going to have a 30-year payback,” and there’s this huge disparity in how you calculate.

And I also might say that when it comes to efficiency, more efficient light bulbs and so forth, or solar energy, you don’t have the continuous maintenance costs that you do with other forms of energy.

Like we’re burning fossil fuels every day. We are importing more and more oil that’s going into power plants. And power plants don’t run themselves. You have to have a lot of highly skilled people running them and then you have to shut them down periodically to maintain them.

So there’s another argument for efficiency and clean energy. They’re the gift that keeps on giving. You put them in and they last generally for at least 10 years, if not 15, if not 20 years.

Kent: Well, I think that’s an important perspective. I always want to look at an issue from a bunch of different angles. You know, turn it upside down, look inside it.

And when it comes to the cost of switching to 100% renewable energy, that’s one where I always want to maintain my critical eye, because, you know, Hawaiian Electric Co. has just released their integrated grid plan, and that basically shows the cost to interconnect all of these renewable energies together.

The plan is like a thousand pages though. It’s really difficult to read through all of that. I had to put down my novel reading and take this up, you know, instead. And at the end of the plan it shows that just the cost of interconnecting all of these renewable systems would be around $9 billion.

And so, that doesn’t actually include the cost to actually build the renewable energy, you know, plants and systems themselves — solar, wind and so on. So far, that cost, as far as I know, hasn’t been calculated — you know, the cost to create all of that.

And that’s partly because they’re not exactly sure which types of energy they want to produce and how much it will cost in the future and so on.

So there’s a lot of assumptions going into these projections, but already we’re seeing really, you know, eye-popping numbers.

Now, Hawaiian Electric says that their renewable plan will actually save people more money in the long run. You know, if oil prices go up and renewable prices stay low as they are now — you know, some renewable energy is low — then in the future, it will save money for ratepayers.

But that’s a big “if” in my mind, because what if the opposite happens? Oil prices go down and, you know, prices for renewable energies skyrocket? Then we might see us losing out on that deal from a financial standpoint.

So I’m just, you know, kind of looking at the assumptions behind the oil spikes, and we’ve had a lot of economists throughout the decades and stock pickers trying to pick the price of oil. It turns out it’s not that easy to predict the price of oil.

Every time there’s widespread agreement that oil is going to go up, it goes down, you know, adjusted for inflation. And so, I’m just wondering how much this will cost and whether our assumptions are, really, if we’re using all the best assumptions in order to calculate this.

Wiig: Well, if you could accurately predict the price of oil, say for a year from now, and you invested accordingly, and you were accurate, you would be a very rich man.

Kent: [laughs] Yeah, that’s true.

Wiig: Because the price of oil is so volatile. Question. What is happening in Russia, which used to be a major, major, major oil supplier? What’s happening with the other oil suppliers? Saudi Arabia turns out to be a very, very iffy entity right now and they are the world’s major oil supplier.

Kent: That’s right.

Wiig: So it’s really, really volatile. But that said, I want to point out to the County of Kauai, where they have led the rest of the state and actually, the rest of the nation, in installing renewable energy, and their cost is actually going down. They are now below the rest of the state.

And I won’t go into the economics of electricity pricing right now, but due to their extensive renewable energy use — and I might say that they also specify efficiency a whole lot — they are really and truly going down, and they are, in terms of stability, resilience, they are less dependent than the rest of us counties on oil.

So, in the event that everything shuts down, they can keep the lights on much more easily than the rest of us can.

Kent: Yeah, that’s true. I think there must be some kind of a principle in renewable energy that points to the fewer people that you’re powering with renewables, the more savings you can realize quicker.

And so, you know, for example, if I put solar panels on my home, I might see savings, you know, this year or next year already. But if you have a large county, like with a million people, like Oahu, and a comparatively small amount of land on that island, it’s much more difficult to find the cost savings that we see on Kauai.

Kauai even has, I think, a much better battery solution with their, I guess, they have a lake that powers a windmill and that helps with the sort of energy storage situation.

But on Oahu, that’s a bit more difficult.

And, you know, Big Island and Maui, Big Island, of course, has geothermal which contributes greatly to their renewable mix. And I think you could actually do geothermal on Maui too, but not on Oahu, or at least it’d be very difficult. So, but you’re right though, that Kauai is a leader in this space.

Wiig: Um-hmm. And I might point out that Oahu and Kauai are approximately the same size. We, as you point out, have a million people. Kauai has only 75,000 people, or 7.5% of our population. So there’s a lot of wide open spaces there. But you’re saying …

Kent: Yeah, that’s a good point. And you know, on Oahu, I’ve noticed that it seems some renewable projects are falling into disfavor from environmentalists themselves. Not all environmentalists, they’re not a big blob, you know.

Environmentalists have many different views on many different things. And when it comes to, I think the Kahuku Wind Farm, for example, a few years ago, that was a really surprising example of environmental protestors at renewable energy. And so, of course, they, I think, didn’t want it in their community.

And the same is true when it comes to solar, which uses lots of land, and, you know, windmills in the ocean, for example; there’s a lot of environmental questions about those things as well.

So now, like I said, if you have a lot of land and a very small amount of people, it may be easier to get around those things, but when you’re land-constrained, it’s much more difficult.

Wiig: Um-hmm. Yep. Absolutely. And here on Oahu, we are definitely land-constrained. There have been proposals to put a solar farm here or there, and other people say, “Wait a minute, that’s farmland that will grow food.” We have this great big push to try to get closer and closer to food [self-sufficiency].

And you can’t cover solar panels. Actually, you can, there’s a proposal to raise the solar panels up at least 8 feet, if not 10 feet. And then under that, you plant shade-loving food, like say lettuce, something like that.

Kent: Oh, I didn’t know about that. That’s interesting.

Wiig: Yeah. But of course, you would be the first to point out that the cost of putting solar farms or solar panels just slightly above the ground versus 10 feet up, that’s going to raise your cost quite a bit there.

Kent: Yeah. And you know, I think in Hawaiian Electric’s integrated grid plan that I talked about, they actually have a land-constrained scenario where they don’t build any offshore windmill farms. And most of the solar is exported to rooftops instead of using lots of land for that.

And so, you know, it’s interesting that they’re actually including that into their main scenarios for, you know, future planning, because it says that, you know, if we can’t even build housing in Hawaii, how are we going to build solar farms, you know? Because they’re both competing for the same land.

And, as you point out, even agriculture is competing for that land too. And of course, open-space activists are competing for that land too. So land is at a premium, and if it takes land to produce renewable energy, then renewable energy will be at a premium too. Unless there’s some solution I’m not seeing, which I’m totally open to.

Wiig: Well, I keep coming back to efficiency, but just to stick with the solar panel analogy, a lot of especially neighbor island resorts have big parking lots for their guests. And these guest cars are sitting in the sun with solar panels above that, boom, you have increased the value of that parking structure. So there’s a payback time in addition to …

Kent: Yeah, that’s true.

Wiig: … use “free” quote-unquote electricity.

Kent: That’s true. I know my wife and I have been looking at trying to buy a new apartment, you know, and of course, we look at the parking lots that have solar panels are always more attractive. You know, it’s just like shady and we just like the shade actually [laughs].

Wiig: Sure. That’s a good reason. Yeah.

Kent: That’s nice, but, of course, there’s a capital cost to that and the HOA [Home Owner’s Association] has to pay for that, and, hopefully, it gets paid back and everything. Most of the problems I think with renewable have to do with the capital investment.

You know, if we just had billions of dollars to invest now, then we’d see those billions paid back at some later date. But the problem is, we don’t have those billions, and paying it back has to take into account the debt service costs, you know. Interest rates right now are very high. And so trying to push off that into debt service just raises the cost even more.

Wiig: Which brings in the possibility of incentives. But you would be the first to point out that, generally, those incentives come from either local or state or federal government, which adds to the governmental costs.

Kent: That’s true, you know. I started my journey looking at renewable energies very interested in trying to figure out how we can find more renewable energies to replace, you know, coal and oil.

And I actually did a tour of renewable energy plants across the U.S. and looked at, you know, wind farms and solar farms and ethanol and methane. And at every single farm or power station, there would be someone who said that they can’t actually profit and make this sustainable without huge government subsidies.

And so it seemed to me that — at least when I did that, which was, you know, more than a decade ago — the subsidies were required, which then just exports the costs, perhaps, to taxpayers.

And so, you know, if we’re trying to save money, it doesn’t make sense to save money on the one hand, and then lose money on the other.

Wiig: I think maybe the exception — and it’s come up in the last 10 years — is the huge swath of great wind regime that goes from Texas, all the way up to Canada, and hopefully includes Mexico and hopefully includes Canada as well, especially where the land is not constrained, i.e., West Texas, just a few cattle roaming around there. It’s hugely cost-effective, even though you have to have these long, long, long extension cords, so to speak, from the desert into the cities of Texas.

Kent: Yeah, that’s true. I mean, where most of the wind is in America is not where most of the people live, unfortunately. [laughs] Unfortunately, for the wind power, it takes a lot of investment in infrastructure to get that power to the places where it needs to go.

And then we’re going back to the capital costs again. But of course, Hawaii wouldn’t be able to plug into that power. You know, we’re apparently the most reliant state on oil of any state in the nation.

And so, we’re not able to — like other states are — to import renewable energy from other states. And so you can’t just flip a switch and get power from New Mexico or something like that.

And so we really, you know, if we’re going to do it, have to do it all on our own, and I’m just wondering what those costs will be.

Wiig: Yeah, well, you’re talking about interconnectedness of different states. Probably the best example is the fact that the Northwest is very, very rich in hydropower and California has something like 40 million people. That’s a lot of electricity. So you have these huge lines exporting electrical energy from the Northwest to California.

But as you pointed out, we just cannot do that.

Kent: Well, you know, maybe if technology changes in the future, it could help some. But, you know, right now, I’m kind of concerned about the trend around the world, towards renewable energies, simply because that means … we’ve never had a time in history where so many people around the world want to make use and invest in renewable energy, such that, you know, the mining that’s required for renewable energy is going to be a mess.

I mean, we’re seeing even electric car companies setting up their own mining shops in other countries around the world just so that they can get the stores of lithium that they need for their batteries, you know, not to mention the lithium that’s needed just for energy storage, you know, like for the grid.

And so, there’s a huge, you know, it used to be a really abundant low-cost thing, lithium, but now with the development of investment and need for demand for batteries, battery power, that is going to see prices, I think, spike.

They may go down in the future. I mean, the one thing about prices going up is then more people try to look for new sources of it. So that sometimes can see prices fall in the future. But anyways, at the moment, we’re seeing a gold rush, a lithium rush.

Wiig: Yeah, a lithium rush, yeah. Especially in this country. I’ve seen an example of Indonesia, and they are really despoiling the environment, by creating huge, huge, huge lithium mines.

Kent: That’s right, yeah. And I am sometimes concerned about whether or not the solution is actually better than the problem. You know, if we’re now creating all these lithium mines — and not just lithium, many other rare earth metals and trying to dig those up — what does that actually mean, if we’re also, you know, continuing to dig up on everything else we’ve dug up in the past, too?

So this just means more mining perhaps, but at the same time, if you have all of these countries switching away from oil, it begs the question again, what the price of oil will do.

Hawaiian Electric is assuming that the price of oil will triple in the future, which is why they say that the status quo energy bill will triple compared to switching to renewables.

Wiig: Would put it from about $80 a barrel to $240 a barrel.

Kent: Yes. That’s right.

Wiig: Not very effective.

Kent: That’s right.

Wiig: Joe, we could continue this …

Kent: Oh, that’s right. [laughs]

Wiig: … invitation for a long, long, long time, but we are both getting the hook. So thank you very much. Joe Kent, Grassroot Institute, and Howard Wiig, “Code Green”. See you in two weeks and farewell.

Kent: Thank you.