by Daniel Pipes

The furor over the Islamic center, variously called the Ground Zero Mosque, Cordoba House, and Park51, has large implications for the future of Islam in the United States and perhaps beyond.

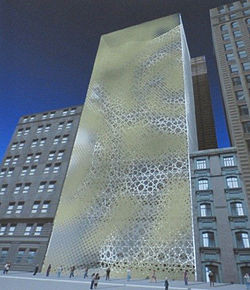

An artist's rendering of the proposed Islamic center near Ground Zero.

An artist's rendering of the proposed Islamic center near Ground Zero.

The debate is as unexpected as it is extraordinary. One would have thought that the event to touch a nerve within the American body politic, making Islam a national issue, would be an act of terrorism. Or discovery that Islamists had penetrated U.S. security services. Or the dismaying results of survey research. Or an apologetic presidential speech.

But no, something more symbolic roiled the body politic – the prospect of a mosque in close proximity to the World Trade Center's former location. What began as a local zoning matter morphed over the months into a national debate with potential foreign policy repercussions. Its symbolic quality fit a pattern established in other Western countries. Islamic coverings on females spurred repeated national debates in France from 1989 forward. The Swiss banned the building of minarets. The murder of Theo van Gogh profoundly affected the Netherlands, as did the publication of Muhammad cartoons in Denmark.

Oddly, only after the Islamic center's location had generated weeks of controversy did the issue of individuals, organizations, and funding behind the project finally come to the fore – although these obviously have more significance than does location. Personally, I do not object to a truly moderate Muslim institution in proximity to Ground Zero; conversely, I object to an Islamist institution being constructed anywhere. Ironically, building the center in such close proximity to Ground Zero, given the intense emotions it aroused, will likely redound against the long-term interests of Muslims in the United States.

This new emotionalism marks the start of a difficult stage for Islamists in the United States. Although their origins as an organized force go back to the founding of the Muslim Student Association in 1963, they came of age politically in the mid-1990s, when they emerged as a force in U.S. public life.

I was fighting Islamists back then and things went badly. It was, in practical terms, just Steven Emerson and me versus hundreds of thousands of Islamists. He and I could not find adequate intellectual support, money, media interest, or political backing. Our cause felt quite hopeless.

Richard H. Curtiss in 1999 predicted American Muslims would follow Muhammad's path to victory.

Richard H. Curtiss in 1999 predicted American Muslims would follow Muhammad's path to victory.

My lowest point came in 1999 when a retired U.S. career foreign service officer named Richard Curtiss spoke on Capitol Hill about "the potential of the American Muslim community" and compared its advances to Muhammad's battles in 7th-century Arabia. He flat-out predicted that, just as Muhammad once had prevailed, so too would American Muslims. While Curtiss spoke only about changing policy toward Israel, his themes implied a broader Islamist takeover of the United States. His prediction seemed unarguable.

9/11 provided a wake-up call, ending this sense of hopelessness. Americans reacted badly not just to that day's horrifying violence but also to the Islamists' outrageous insistence on blaming the attacks on U.S. foreign policy and later the election of Barack Obama, or their blatant denial that the perpetrators were Muslims or intense Muslim support for the attacks.

American scholars, columnists, bloggers, media personalities, and activists became knowledgeable about Islam, developing into a community, a community that now feels like a movement. The Islamic center controversy represents its emergence as a political force, offering an angry, potent reaction inconceivable just a decade earlier.

The energetic push-back of recent months finds me partially elated: those who reject Islamism and all its works now constitute a majority and are on the march. For the first time in fifteen years, I feel I may be on the winning team.

But I have one concern: the team's increasing anti-Islamic tone. Misled by the Islamists' insistence that there can be no such thing as "moderate Islam," my allies often fail to distinguish between Islam (a faith) and Islamism (a radical utopian ideology aiming to implement Islamic laws in their totality). This amounts not just to an intellectual error but a policy dead-end. Targeting all Muslims conflicts with basic Western notions, lumps friends with foes, and ignores the inescapable fact that Muslims alone can offer an antidote to Islamism. As I often note, radical Islam is the problem and moderate Islam is the solution.

Once this lesson is learned, the new energy brings the defeat of Islamism dimly into sight.

Mr. Pipes (www.DanielPipes.org) is director of the Middle East Forum and Taube distinguished visiting fellow at the Hoover Institution of Stanford University. © 2010 by Daniel Pipes. All rights reserved.