Viewpoint: Chemophobia epidemic—Fanning fears about trace chemicals obscures real risks and ‘damages public health’

by Jon Entine, Genetic Literacy Project, October 24, 2018

When is a chemical dangerous?

This is not a question we consciously ask ourselves much, but in fact, we interrogate the world and our safety unconsciously dozens of time each day about it. Is our child’s plastic sippy cup made with dangerous chemicals? Does the cleaner we are using on our car give off dangerous fumes? What about the spray to kill dandelions?

It’s also an issue constantly in the headlines. Earlier this week (October 24) an article appeared in the JAMA [Journal of America Medical Association] Internal Medicine journal claiming that people surveyed who primarily ate organic food were less likely to contract cancer—and it postulated that pesticide residues in conventional might be the causal factor. [more on that study below]

How do people assess hazard and risk? How safe is safe?

Media perceptions and government regulations are often shaped by a fervor fed by misconceptions about the widespread dangers of common chemicals. Consider the word “pesticide.” Sounds scary. After all, synthetic and natural pesticides kill unwanted pests such as insects, weeds, fungi and rodents.

But advocacy groups, many hostile to conventional agriculture, mostly refer to pesticides pejoratively, assuming anything that can kill an insect or weed can also do a lot of damage to humans exposed to trace residues. This is almost never true. In fact, it is not even possible for some pesticides to harm humans. For example, it’s biologically impossible for Bt bacterium proteins that are found in soil and plant leaves worldwide and which are sprayed widely by organic farmers to kill certain insects and are bioengineered into insect-resistant seeds to harm humans or animals because mammals do not have the same receptors or gut conditions as insects. But that doesn’t stop the hysteria or misrepresentations from advocacy groups who claim food grown from Bt seeds are chemically harmful to humans (while irrationally exonerating Bt spraying by organic farmers).

Pesticides are regularly, and irrationally, blamed for all sorts of problems—from environmental pollution to hormonal disruption to cancer. One prime example? Glyphosate.

Just this week, an appellate judge upheld a jury verdict blaming the herbicide found in Monsanto’s Roundup® and generic formulations for a California groundskeeper’s cancer. As the judge noted, the ruling came despite hundreds of reviews and studies, most by government regulatory oversight agencies and independent scientists, that has found the popular weed killer to be safe as used. The judge cut the jury’s punitive damage award by 84% to $39 million after hinting during a prior hearing that she was considering throwing out the verdict altogether because of a lack of independent research linking glyphosate to cancer.

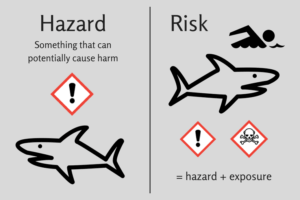

The verdict turned on a June 2015 evaluation by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) that glyphosate was “probably carcinogenic to humans.” It was not a finding of “risk” but of “hazard”—and did not take into account exposure. IARC put glyphosate in the same category as coffee and salted fish. It was deemed less possibly carcinogenic than alcohol, which is very hazardous and can lead to cancer—if you are exposed to (consume) extraordinary amounts of it. The IARC evaluation was also plagued by conflict of-interest charges and allegations uncovered during a Reuters investigation that data was manipulated or left out. Also, it emerged during the trial that Christopher Portier, the chief IARC investigator, had negotiated to be a well-paid consultant ($160,000 in disclosed fees) before the hazard decision was even announced.

Chemophobia may lead to real risks

The fact is that almost all chemicals we encounter on a regular basis have undergone reviews of one kind or another and are safe as used. Yet people still believe that somehow one government agency or another “missed something” or that it’s in cahoots with “big business” and has fudged the safety data.

An illusion also has developed that chemicals can be divided into categories of “safe” versus “unsafe.” But any substance, even food and vitamins, can be harmful if we consume too much of it. Safety is relative, depending on the frequency, duration and magnitude of exposure.

To put into context how askew this debate has gone, let’s look at the supposed risk that pesticides cause pediatric cancer. No issue could be more emotionally charged.

A study published in August 2018 in The Lancet Oncology examined the incidence of pediatric cancer from 1991 to 2010. It was a gigantic study that included 1.3 billion person-years. (One “person-year” is an epidemiological term that refers to one person being studied for a period of one year.) The study found cancer rates have stabilized over the past decade after minimal increases of 1 percent in the two previous decades. As for the impact of pesticides, in an accompanying commentary, Belgian cancer epidemiologist Philippe Autier wrote:

In 2014, the quantities of pesticide sales per capita were about three times greater in Spain, Italy, and France than in Sweden or the UK. If increasing cancer incidence trends were due to pesticides, dissimilarities in incidence trends for leukemia and lymphoma would be expected between European regions, which was not the case.

Put another way, if pesticides were a serious driver of pediatric cancer, then countries that use more pesticides are likely to have more cases of pediatric cancer. But they don’t. Therefore, pesticides probably do not cause pediatric cancer—which is what almost all scientists believe, rejecting hysteria anti-trace pesticide campaigns by activist organizations such as the Environmental Working Group and its infamous Dirty Dozen campaign.

Related article: Hawaii County council keeps anti-GMO bill alive

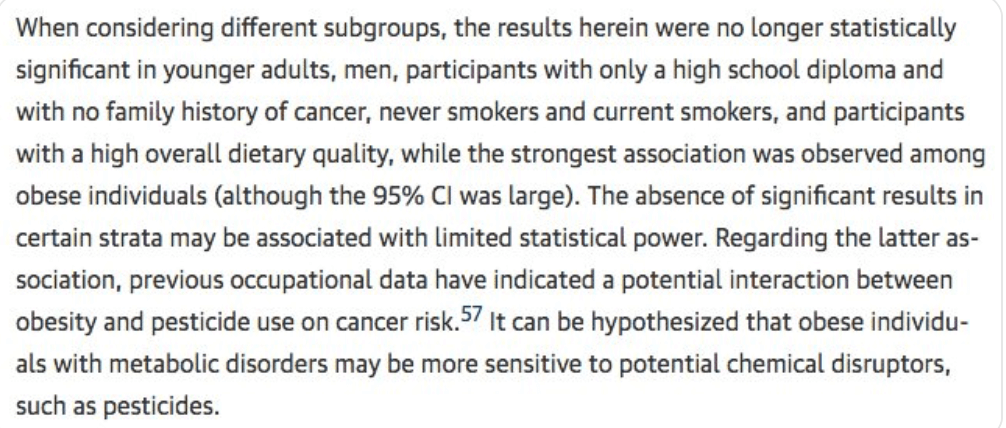

More fears, stirred by headlines in newspapers and media sites around the world, emerged this week with the publication of a French study suggesting that trace pesticides in conventional food might cause cancer —at least that’s what the authors, who propose that people might consider switching to organic food, claim. They posed the question: “What is the association between an organic food–based diet (ie, a diet less likely to contain pesticide residues) and cancer risk?” Their conclusion: One possible explanation for the negative association between organic food consumption and cancer risk is that the prohibition of pesticide use in organic production methods results in lower contamination levels. The results suggest, they said, that that “attention should now turn to the potential chronic effects of low-dose pesticide residue exposure from diet as well as potential cocktail effects at the general population level.”

While some scientists praised the study for raising a yellow flag about pesticide residues, many independent epidemiologists and statisticians eviscerated it. It was a muddle based on self-reporting and only of French residents who polls show are enraptured by organic food and hostile to many modern agricultural practices that include synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. Only 2% of the respondents got cancer, which itself is an extraordinary small number.

Organic eaters in the study were more likely to be more affluent (36% likely to be less poor), have a college degree, eat more vegetables and less processed meat, have a healthier diet overall and they are less likely to be overweight and were more active––confounding facts. The authors claimed they adjusted for some factors but not all and their methodology for adjusting is not transparent.

Oddly, the authors made the claim that the link to cancer for those in poverty was not causal while it was for eating organic food, what seems like an arbitrary conclusion. In one startling paragraph, the authors note that the correlation to cancer did not hold for younger adults, never or current smokers, people who eat healthy food, and, remarkably, for all men.

What a hodgepodge of questionable science! Correlation studies are problematic at best with authors frequently cherry-picking associations that fit pre-conceived notions (it should be noted that the lead author in the study is a well known proponent of organic food) and rejecting or not even considering correlations that might confound the results. According to Tom Sanders, professor emeritus of Nutrition and Dietetics at King’s College London:

This an observational study, not a controlled trial. The participants who reported eating organic food most frequently were more likely to be non-smokers, had a lower body mass index (less obesity) and drank less alcohol, all factors that would be expected to result in fewer cases of cancer in this group. Their conclusion, that promoting organic food in the general population could be a promising cancer preventive strategy, is overblown.

[Editor’s note: Read other scientists’ analyses of this study at the UK Science Media Centre]

This is yet one more study that appears to have been designed to confirm a preconceived viewpoint.

The bottom line is that more research is necessary to uncover the causes of cancer but there remains no persuasive evidence that trace residues are a key driver. The public and advocacy group obsession with the alleged dangers of trace chemicals found in common usage is unhealthy. Serious health challenges need to be forcefully confronted, but the resources devoted to challenging and removing relatively innocuous chemicals in exchange for substitutes––usually substances that have often not been scrutinized as much as the chemicals they would replace and thus confer an illusion of safety––divert us from addressing known health risks. This chemophobia can result in the opposite of what was intended: a decrease rather than an increase in public health.

---30---

Jon Entine is a freelance journalist, author of “Scared to Death: How Chemophobia Threatens Public Health” and other books, and founder and executive director of the Genetic Literacy Project. Follow him on Twitter @JonEntine