A Visual Guide to Unemployment Benefit Claims

by Jared Walczak and Tom VanAntwerp, Tax Foundation, April 9, 2020

According to Thursday’s data release, weekly initial unemployment benefit claims hit the highest level in U.S. history for the third week in a row, with 6,203,359 people filing for unemployment—slightly higher than the 6,015,821 who filed last week. Prior to the current crisis, the highest one-week unemployment claims as a percentage of everyone in the unemployment insurance system (those currently in “covered” employment plus those claiming benefits) was 1.36 percent, in January 1975. During the Great Recession, the one-week peak was 0.68 percent in January 2009. During the week ending April 2, it reached 3.89 percent.

Approximately 8.4 percent of the U.S. civilian labor force has now applied for or is receiving unemployment compensation benefits (through April 2, the latest data). The previous high was 7.9 percent early in 1975 during a recession, with a Great Recession peak of 4.8 percent between February and April 2009. Entering March 2020, unemployment claims as a percentage of the civilian labor force stood at 1.4 percent.

Mandatory business closures and shelter-in-place orders have radically accelerated job losses compared to the steadier pace of layoffs in prior recessions, meaning these claims likely represent a far greater share of the ultimate total than did any week’s claims during the Great Recession. But the numbers are still staggering, with every likelihood of sobering numbers in coming weeks as well.

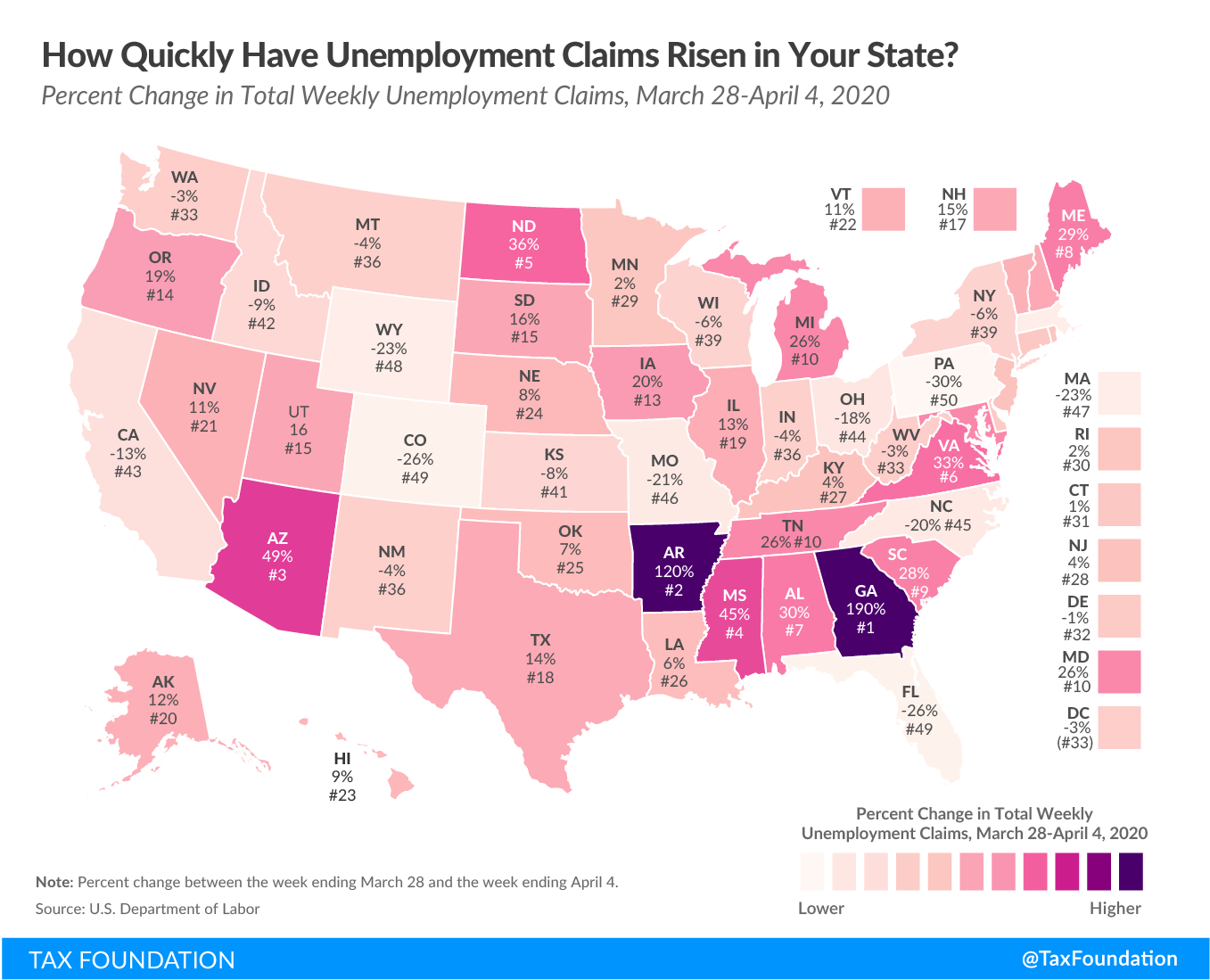

Our interactive tool allows you to see how the most recent week’s initial unemployment compensation claims in each state compare to average and peak weekly claims during the Great Recession. States vary in how quickly they process and report claims, so some states are “ahead” of their peers in reporting substantial increases, and differentials across states may be questions of timing rather than effects of the economic contraction.

Many states are woefully unprepared for the magnitude of the challenge ahead. Entering the crisis, 21 states’ unemployment compensation trust funds were below the minimum recommended solvency level to weather a recession. Six states had less than half the minimum recommended amount, representing 37 percent of the U.S. population.

Crucially, a solvency level of 1 indicates the ability to pay out claims for one year during a Great Recession-like event, and as of April 2, nearly 14.4 million people had filed for unemployment, 283 percent of the worst Great Recession level. A level of 1 now suggests the ability to pay out current claims for only a little over 18 weeks. A state like California, with a solvency level of 0.21, can cover less than four weeks before drawing upon other funds or borrowing from the federal government. Federal loans must be paid back, potentially with interest, and can eventually yield higher federal unemployment insurance tax rates on businesses in that state.

As more firms lay off employees and unemployment increases, states’ unemployment insurance taxes will rise on businesses that can least afford to pay. As states receive federal assistance to aid with unemployment benefits, it may be appropriate to provide some measure of relief to businesses as well, particularly to the extent that their layoffs were precipitated by business closure orders.

Explore your state’s data on our interactive tool >>> HERE

* * * * *

Compensation Trust Funds Could Run Out in Mere Weeks

by Jared Walczak, Tax Foundation, April 9, 2020

Six states, which collectively account for over one-third of the U.S. population, are currently in a position to pay out fewer than 10 weeks of the unemployment compensation claims that have already come in since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic—including those they’ve already begun to pay out. California is in the worst shape, with only about 26 days’ worth of funding in its unemployment compensation trust fund. Overall, only six states would be able to pay out benefits for a year or more based on current unemployment insurance (UI) benefit claims levels.

The U.S. Department of Labor assesses the health of state UI funds with several measures. One is the Reserve Ratio, which looks at the trust fund balance as a percentage of a state’s total annual wages. Minimum adequate solvency entering a recession is calculated by dividing the Reserve Ratio by what is called the Average Benefit Cost Rate, which represents the average of the three highest rates of benefits the state had to pay out (as a percentage of state wages) over the past 20 years. If this yields a solvency level of 1.0 or greater, the state is deemed to have adequate UI funding to weather a recession.

Unfortunately, UI claims during the current crisis are dramatically higher than they were during the Great Recession. Initial and continuing claims for the week ending April 4 (most recent data) stand at 14.38 million—283 percent of averages for the three years used to calculate solvency levels.

It is possible to take states’ reported solvency levels at the start of the year, along with claims data for each state’s own worst three years, and match those against the most recent initial and continuing claims data to obtain an estimate of how many weeks of benefits a state could pay out based on those who have applied for or are currently receiving unemployment insurance benefits.

If anything, this estimate is generous, as it only takes into account claims filed through April 4 (due to the timing of data releases) and does not adjust for the degree to which these states’ funds have already been drawn down over the past two weeks.

When states exhaust their trust funds, they must look to other sources of funding, either within their own state budgets or through loans from the federal government, which must ultimately be paid back—in some cases with interest.

The 31 states with solvency levels of 1.0 or higher may borrow without interest, at least initially; states with lower solvency levels will incur interest payments. Eventually, should states take too long to repay these loans, technically called Title XII advances, in-state employers will face higher federal unemployment insurance taxes to compensate for their state’s indebtedness.

The federal government, as part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, is providing federal funding to incentivize states to end one-week waiting periods, providing an additional $600 a week to each state unemployment insurance beneficiary, and offering extended benefits once state benefits run out—but states must still come up with the funding for regular benefits, and unfortunately, many are woefully unprepared to do so.