New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, center right, and New Hope Baptist Church pastor Joe Carter, right, listen to former drug addicts talk during a summit on drug addiction. Millions of newly eligible adults in New Jersey and other states that are expanding Medicaid will have access to addiction treatments this year, many for the first time. (AP)

States Gear Up to Help Medicaid Enrollees Beat Addictions

by Christine Vestal, Pew Charitable Trust, January 13, 2015

Under the Affordable Care Act, millions of low-income adults last year became eligible for Medicaid and subsidized health insurance for the first time. Now states face a huge challenge: how to deal with an onslaught of able-bodied, 18- to 64-year olds who haven’t seen a doctor in years.

“It took a lot of time and effort to enroll everyone, particularly those who were new to the system,” said Matt Salo, director of the National Association of Medicaid Directors. “The next big step, and the biggest unknown, is finding out exactly how this newly insured population will use the health care system.”

Until now, the vast majority of Medicaid beneficiaries were pregnant women, young children, and disabled and elderly adults. Relatively few able-bodied adults without children qualified, so states did not set up their Medicaid programs to treat them.

The newly insured, most of them young adults, have different needs. Though not as sick as existing Medicaid beneficiaries, the newcomers are more likely than the general population to have undiagnosed and untreated chronic illnesses such as diabetes and heart disease.

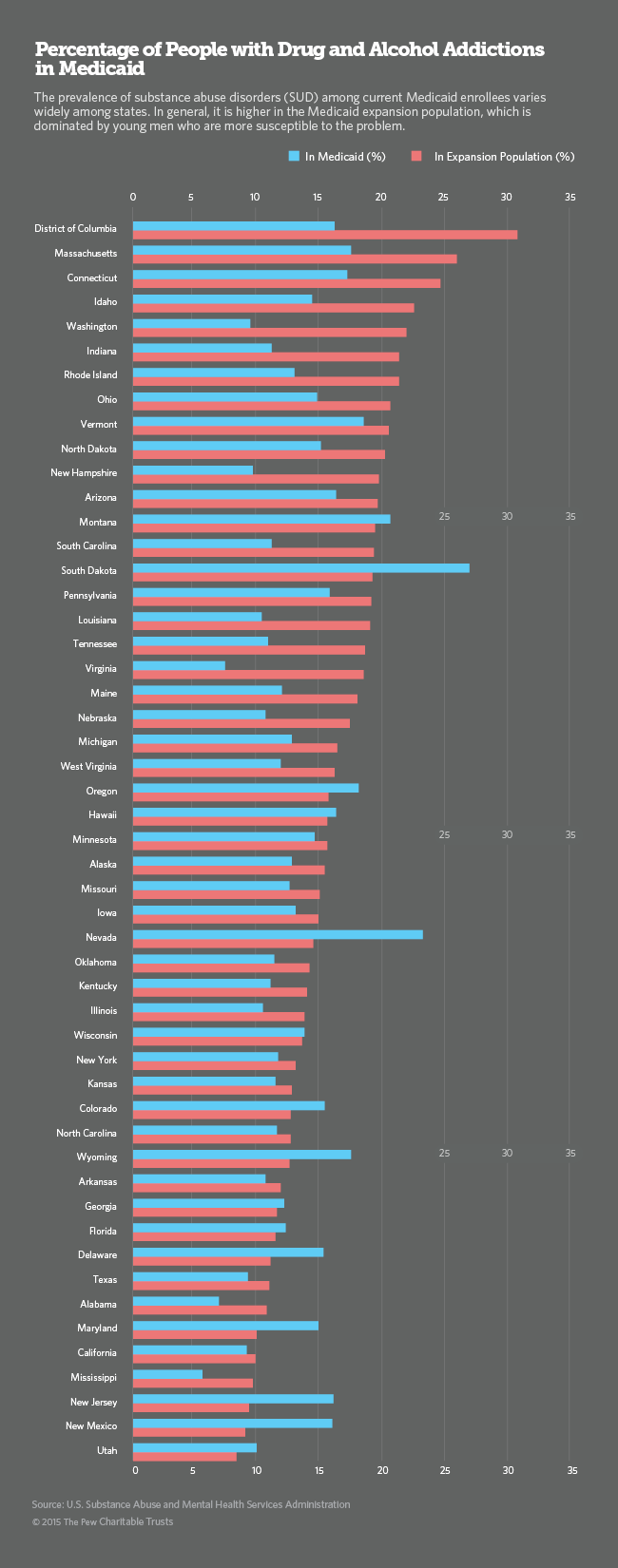

The starkest difference between the new population and the old one, however, is that the new enrollees have much higher rates of drug and alcohol addiction and mental illness.

Of the estimated 18 million adults potentially eligible for Medicaid in all 50 states, at least 2.5 million have substance-abuse disorders. Of the 19 million uninsured adults with slightly higher incomes who are eligible for subsidized exchange insurance, an estimated 2.8 million have substance-abuse problems, according to the most recent national survey by the U.S. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

In addition to increasing the number of people with health insurance, the ACA for the first time made coverage of addiction services and other behavioral health disorders mandatory for all insurers, including Medicaid. As a result, the number of Medicaid enrollees receiving addiction services is expected to skyrocket over the next two years.

Although Medicaid and other state and federal programs have provided care for people with serious mental illnesses, coverage of addiction treatments has been spotty. Optional under Medicaid until now, coverage in most states was limited, typically just for pregnant women and adolescents.

“It’s the biggest change in a generation for addiction services,” said Robert Morrison, executive director of the National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors. “Comprehensive addiction programs didn’t exist in Medicaid until now.”

Big Demand, Short Supply

Behavioral health professionals typically earn far less than other health care providers, in part because few insurers have been willing to pay for their services. Many who enter the profession quickly abandon addiction treatment for more lucrative specialties. The result: a national shortage of addiction-treatment providers.

Now, as billions of dollars from Medicaid and other insurers are becoming available, behavioral health experts say it will take time, training and new state licensing policies to expand the pool of providers to meet the new demand.

The first step for states is to create ACA-compliant addiction-benefit packages and fee structures to compensate the mostly small businesses that currently offer detox and rehabilitation services. Over time, states are expected to loosen behavioral health licensing requirements and offer professional and business training to promote an expansion of the workforce.

A Growing Population

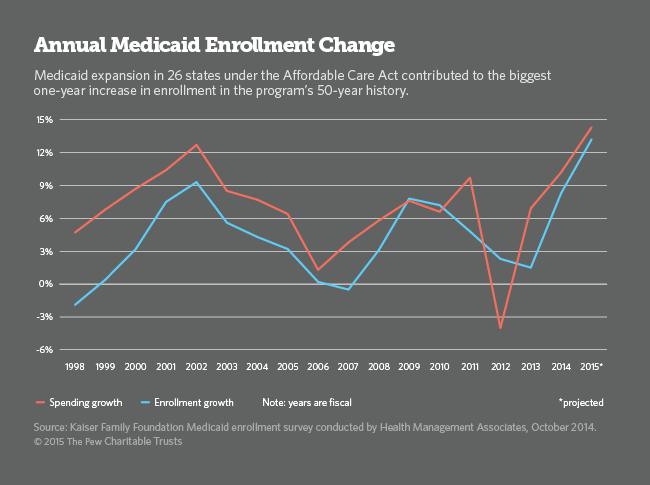

So far,eight million people have signed up for exchange insurance policies and 7.2 million have enrolled in Medicaid since last year, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Because Medicaid enrollment is continuous, those numbers are expected to rise substantially this year and next.

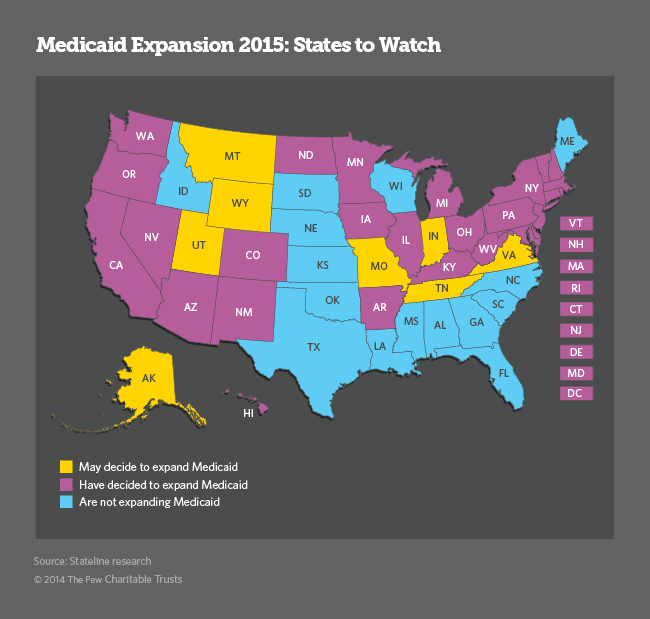

Under the ACA, states have the option of expanding Medicaid to adults with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level ($11,670 for an individual). The federal government will pay the entire bill for 2014 through 2016, and then it will pay a declining share over the following three years, and 90 percent thereafter. So far, only 27 states have taken up the option, but several Republican-led states are considering it, potentially adding millions more adults to the Medicaid rolls this year.

Fourteen percent of the low-income adults who are newly eligible for Medicaid under the ACA have drug and alcohol addictions, compared with 10 percent in the general population. Because the new Medicaid population is dominated by young, single men — a group at much higher risk for drug and alcohol abuse — Medicaid enrollees needing treatment could more than double, from 1.5 million before last year’s Medicaid expansion to about 4 million in the next five years.

In 2012, about 22 million Americans were classified with substance-abuse disorders. Of those, 2.8 million had problems with both alcohol and drugs, 4.5 million had problems with drugs but not alcohol, and 14.9 million had problems with alcohol only. Only 2.5 million received help, according to the most recent National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

In the coming months, states and the federal government will begin releasing data, based on Medicaid claims, showing how many newly eligible Medicaid enrollees are using their new health cards, and for what. So far, there is only anecdotal evidence and limited state data.

In California, for example, 10,568 newly enrolled beneficiaries had signed up for addiction services by May, an increase of more than 30 percent under the state Medicaid program. The number of adults in Washington state’s Medicaid treatment facilities doubled in the first six months of the year. Vermont Medicaid officials also reported a substantial increase in the number of Medicaid enrollees seeking treatment.

Colorado’s director of health policy and planning, Susan Birch, said Medicaid officials there feared the worst but were “delighted” to find that the 290,000 newly enrolled adults were healthier than expected. “We budgeted as if they would be in more of a dire, acute stage,” she said. “People aren’t coming in as sick as we thought and they’re not staying as long in our system,” Birch said.

Part of the reason some Medicaid agencies are initially seeing milder cases of addiction is that many of the heaviest and most prolonged drug and alcohol users in Colorado and elsewhere have ended up in jails, prisons and emergency rooms, or entered state health care systems as indigents.

In addition, many states have covered a limited number of addicted adults under state-funded programs aimed at helping their poorest residents with severe mental illness and addictions. As a result, the number of new Medicaid enrollees with severe addiction cases, those that already have caused serious health problems, could be relatively low.

But states are no longer willing to wait for people to walk into a local clinic and ask for help. Instead, many state Medicaid agencies are working with primary-care physicians and hospitals to reach people with addictions before their physical and mental health crumbles and their work and family relationships fall apart.

“We’re talking about those that are pre-catastrophic cases,” Birch said. “We hope we can keep people from getting worse before they get into the organ transplant and suicide realm,” she said. Colorado has begun a statewide collaboration between primary-care doctors and behavioral health specialists to make sure that happens.

A Huge Payoff

Much of the current emphasis on addiction services stems from medical research showing that individuals with untreated drug and alcohol disorders are among the heaviest users of the health care system, contributing to a substantial share of rising Medicaid, Medicare and private health care spending. Mounting evidence also shows physical health care costs decline dramatically when people with substance addictions get treatment. The longer they maintain sobriety, the lower their medical bills are.

“All of a sudden there’s a great deal of interest in people who are ‘high utilizers’ of emergency rooms and who don’t have any connection to health care,” said Art Schut, CEO of Arapahoe House, Colorado’s largest provider of drug and alcohol addiction services. “Many of the people we used to deal with didn’t have a primary care physician, and we couldn’t get them one,” he said.

A major goal for nearly all states is to find ways to better integrate physical and behavioral health, including addiction treatments. Now that addiction treatment is an integral part of Medicaid’s overall health plan, Schutt says he expects health outcomes to improve and costs to go down.

“We’re at the point where we’re actually treating substance use illness the way we treat other illnesses. There’s a realization in the commercial and public marketplace that health outcomes are important and that SUD (substance use disorder) treatment contributes significantly to overall health. It’s transformational for health care, not just substance use,” he said.

In Washington state, for example, the health agency invested in a drug and alcohol treatment program in 2005 and found that for every dollar spent, the state saved $2 in medical and nursing facility costs in the first four years.

“It’s hard for Medicaid directors watching mounting claims for addiction medications and treatments to take into account the expenses they’re not seeing,” said Morrison, director of the state alcohol and drug abuse group. But he said nearly every state agency is on board with the concept that addiction treatments, including medications, do result in substantial overall health care savings.

Colorado’s Schut says most providers already are trying to integrate physical and behavioral health, but until Medicaid agencies develop better financing options, their efforts will be hard to maintain. “The ACA opportunities are a dream come true,” he said, “but we’re not quite there yet.”