Nine States Began the Pandemic With Long-Term Deficits

by Joanna Biernacka-Lievestro & Alexandre Fall PEW Foundation, December 16, 2022

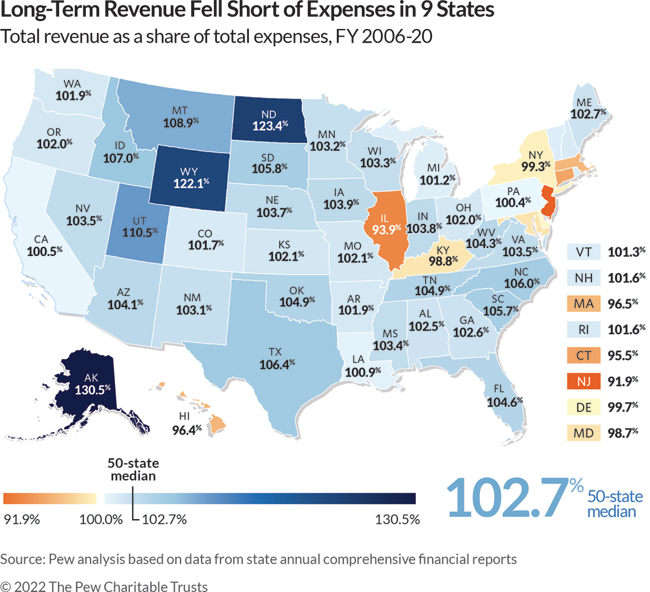

Twenty states recorded annual shortfalls in fiscal year 2020, when the coronavirus pandemic triggered a public health crisis, a two-month recession, and substantial volatility in states’ balance sheets. States can withstand periodic deficits, but long-running imbalances—such as those carried by nine states—can create an unsustainable fiscal situation by pushing off some past costs for operating government and providing services onto future taxpayers.

States are expected to balance their budgets every year. But that’s only part of the picture of how well revenue—composed predominantly of tax dollars and federal funds—matches spending across all state activities. A look beyond states’ budgets at their own financial reports provides a more comprehensive view of how public dollars are managed. In fiscal 2020, a historic plunge in tax revenue collections and a spike in spending demands were met with an initial influx of federal aid to combat the pandemic. The typical state’s total expenses and revenues grew faster than at any time since at least fiscal 2002, largely thanks to the unprecedented federal aid. But spending growth outpaced revenue growth in all but five states (Idaho, Maryland, Missouri, South Dakota, and Virginia). And 20 states recorded annual shortfalls—the most since 2010 and four times more than in fiscal 2019.

Despite the sudden increase in annual deficits, most states collected more than enough aggregate revenue to cover aggregate expenses over the long-term. But the nine states that had a 15-year deficit (New Jersey, Illinois, Connecticut, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Maryland, Kentucky, New York, and Delaware) —or a negative fiscal balance—carried forward deferred costs of past services, including debt and unfunded public employee retirement liabilities. Between 2006 and 2020, New Jersey accumulated the largest gap between its revenue and annual bills, taking in enough to cover just 91.9% of its expenses—the smallest percentage of any state. Meanwhile, Alaska collected 130.5%, yielding the largest surplus. The typical state’s revenue totaled 102.7% of its annual bills over the past 15 years.

Zooming out from a narrow focus on annual or biennial budgets—which may mask deficits as they allow for shifting the timing of when states receive cash or pay off bills to reach a balance—offers a big-picture look at whether state governments have lived within their means, or whether higher revenue or lower expenses may be necessary to bring a state into fiscal balance.

Download the data

State highlights

States’ performance is analyzed from two perspectives: First, the 15-year lump sum of revenue relative to expenses, to uncover states’ ability to bring in sufficient funds to cover costs over the long term; and second, the year-by-year record for each state, to identify how often it experienced shortfalls.

Comparing states’ revenue—comprising much more than tax dollars—and expenses, in aggregate and year-by-year totals from fiscal 2006 to 2020, shows:

After New Jersey, Illinois had the largest deficit with aggregate revenue able to cover only 93.9% of aggregate expenses. They were the only two states with total shortfalls exceeding 5% of total expenses, and the only ones with annual deficits in each of the 15 years.

Additional states with symptoms of structural deficits were Connecticut (95.5%), Hawaii (96.4%), Massachusetts (96.5%), Maryland (98.7%), Kentucky (98.8%), New York (99.3%), and Delaware (99.7%). All but Delaware experienced deficits in at least 10 of the 15 years.

Alaska accumulated the largest 15-year surplus (130.5%). Although Alaska’s balance is high, revenue has been lower and the state has pulled back on spending compared with earlier in the decade.

Other states with the largest accumulated surpluses since fiscal 2006 were North Dakota (123.4%), Wyoming (122.1%), Utah (110.5%), and Montana (108.9%). Resource-rich states tend to acquire large surpluses in boom years that can help cushion shortfalls when oil or mining revenue decline.

Aside from Montana, which was the only state to end each year with a surplus, 10 recorded just one deficit over the 15 years examined: Idaho, Iowa, North Carolina, North Dakota, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, and Virginia.

Year-by-year trends

Changes in the economy can move a state’s annual revenue and expenses out of balance, as can policy decisions such as tax or spending changes.

Looking at states’ balances year by year, shortfalls mainly occurred during and immediately after the Great Recession, suggesting that most states’ challenges were temporary. As the nation’s economic recovery took hold, a majority of states balanced their books and have kept them in the black. Still, 15 states in fiscal 2016 and 2017 failed to amass enough revenue to cover their annual expenses, as many slogged through the weakest two years of tax revenue growth—outside of a recession—in at least 30 years. (See the “State trends” tab.)

Only five states recorded annual shortfalls in fiscal 2019, the last full year before the COVID-19 recession, following seven states with deficits in fiscal 2018. In both years, nearly every state experienced tax revenue gains that drove widespread budget surpluses. However, it is unclear whether more states’ books achieved balance strictly because of stronger fiscal performance; accounting rules effective in 2018 changed how states estimated their unfunded retiree health care costs, lowering expenses for some, at least on paper. So fiscal 2018 and 2019 results are not directly comparable with those for previous years.

Following the volatile fiscal year 2020 that threw 20 states’ finances out of balance, states reaped the benefits of a strong tax revenue rebound and unprecedented levels of federal aid in fiscal 2021 and 2022. Although state spending also continued to grow at a rapid pace, widespread surpluses and record reserves suggest that annual balances strengthened. But looking ahead, high levels of uncertainty remain, as economic conditions weaken and the temporary impacts of federal stimulus fade.

Why fiscal balance matters

This fuller picture of states’ financial activities—capturing all but those for legally separate auxiliary organizations, such as economic development authorities or some universities—is drawn from their audited annual comprehensive financial reports. These reports attribute revenue to the year it is earned, regardless of when it is received, and expenses to the year incurred, even if some bills are deferred or left partially unpaid. This system of “accrual accounting” offers a different perspective of state finances than budgets, which generally track cash as it is received and paid out. Accrual accounting captures deficits that can be papered over in the state budget process, even when balance requirements are met, such as by accelerating certain tax collections or postponing payments to balance the books.

Accounting for funds as the financial reports do is like a family reconciling whether it earned enough income over 12 months not just to cover costs paid with cash but also to pay off credit card bills and stay current on car or home loan repayments, rather than pushing some charges off to the future.

A state whose annual income falls short generally turns to a mix of reserves, debt, and deferred payments on its obligations to get by. Conversely, when a state’s annual income surpasses expenses, the surplus can be directed toward nonrecurring purposes, including paying down obligations or bolstering reserves—or new or expanded services that create recurring bills.

Like families, states can withstand periodic deficits without endangering their fiscal health over the long run. In fact, all but one state (Montana) had one or more years in the red. But chronic shortfalls—as with New Jersey and Illinois each year since at least fiscal 2002—are one indication of a more serious structural deficit in which revenue will continue to fall short of spending absent policy changes. Without offsetting surpluses, long-running imbalances can create an unsustainable fiscal situation.

Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports broaden the scope of financial reporting beyond state budgets to capture all funds under control of the state government, including revenue and spending from related units, such as utilities and state lotteries. This produces a more comparable set of state-to-state data. All primary government operations were included in this analysis. “Component units,” such as economic development authorities or public universities, were excluded when states classified them separately.

Although all states file audited and nationally standardized financial reports, they are mostly used by credit rating agencies and other public finance analysts, while most state finance discussions center on budgets.

Examining aggregate revenue as a share of aggregate expenses—that is, all revenue and all expenses from fiscal 2006 to 2020, each adjusted for inflation—provides a long-term perspective that transcends temporary ups and downs. This approach allows surplus funds collected in flush years to balance out shortfalls in others.

Importantly, just because a state raised enough revenue over time to cover total expenses does not necessarily mean that it paid each bill. For example, a state might have brought in surpluses nearly every year while falling behind on annual contributions to its pension system and electing to use the money for other purposes. So this measure gauges states’ wherewithal but does not reconcile whether revenue was used to cover specific expenses. Collecting more revenue than expenses over the long term is a necessary but insufficient condition of fiscal balance. Further insights can be gleaned from examining states’ debt and long-term obligations.

A negative fiscal balance can be one indication of a structural deficit in a state, but there is no consensus on how to measure a circumstance in which revenue will continue to fall short of spending absent policy changes. Some states, for example, diagnose the existence of a structural deficit by comparing cash-based recurring general fund revenue to recurring expenditures under normal economic conditions. However, such data are not available on a 50-state basis.

Download the data to see individual states’ inflation-adjusted revenue and expenses for each fiscal year from 2006 to 2020. Visit Pew’s interactive resource Fiscal 50: State Trends and Analysis to sort and analyze data for other indicators of states’ fiscal health.

---30---