Are We Hitting Our Targets? A Look at Hawai‘i’s GHG Emissions

From UHERO, August 11, 2021

By Makena Coffman, Maja Schjervheim, and Paul Bernstein

Over the past three years, the State of Hawai‘i Department of Health has released a Hawai‘i Greenhouse Gas Emissions Report. This year’s report added an inventory for 2017, as well as projections through 2030 based on existing policies and trends. UHERO collaborated with ICF on this project and estimated future emissions and their uncertainty.

The rationale for these reports is to measure GHG emissions within the state and track progress on Hawaii Act 234 (2007). This act set a target to reduce statewide GHG emissions to 1990 levels by 2020, excluding aviation-related emissions. In 2018 the state also passed Act 15 (2018) that sets a goal of making Hawaiʻi carbon “net-negative” by no later than 2045. The reports also estimated the GHG impact of the state’s renewable portfolio standard (RPS) (HRS § 269-91) that requires electric utilities to meet 100% of net sales through renewables by 2045, with intermediary targets in earlier years. At the time of enactment, the RPS and carbon net-negative goals were the most ambitious of their kind among US states. Is it possible for Hawaiʻi to live up to its ambitions?

(CLUE: Look at the difference between the reality and the projections and ignore the silly blue line.)

(OTHER CLUE: ‘Domestic’ aviation means Hawaii inter-island, not ‘domestic’ within the USA. If trans-oceanic aviation were included, Hawaii would be nowhere near the goal--so they ‘solve’ the problem by ignoring it.)

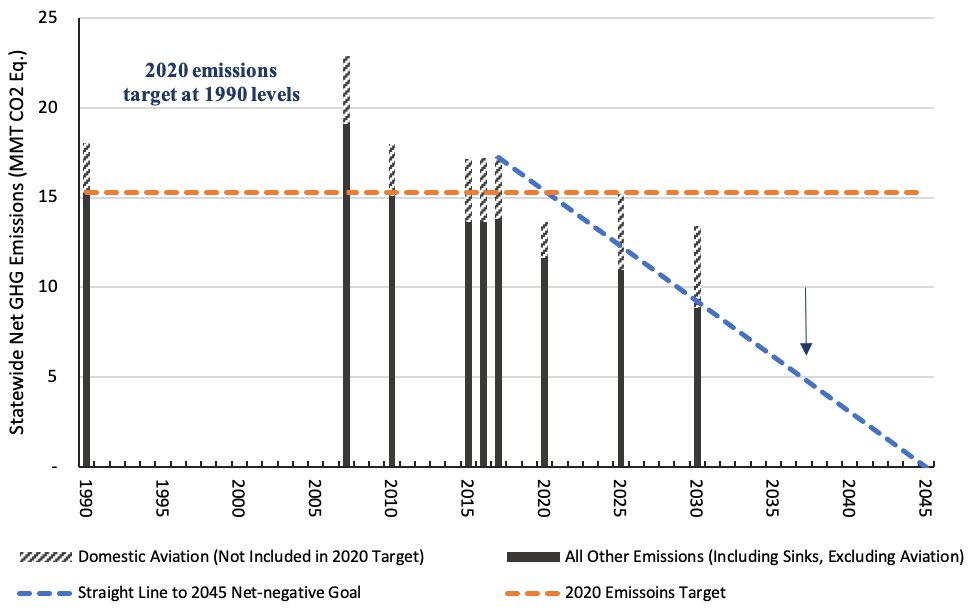

Figure 1. Hawaii GHG Emissions Inventories (1990, 2007, 2015, 2016 and 2017) and Projected Estimates (2020, 2025 and 2030) (MMT CO2 Eq.)

Let’s start with affirming that Hawai‘i met its 2020 target to reduce non-aviation emissions to 1990 levels – though clearly 2020 was an abnormal year. But, as Figure 1 illustrates, Hawai‘i met its goal as early as 2010 in the wake of the Great Recession. Given that this was only three years after adoption, and there had been no meaningful policy changes implemented by then, it is fair to say that the 2020 target was, in hindsight, simply unambitious. Nevertheless, the 2020 target fueled conversations about GHG abatement in the state and served as the precursor to the target of net-negative before 2045—a goal that is much more ambitious and up to par with what the climate crisis requires.

But ambition only gets us so far and projections indicate that progress is too slow. Drawing a straight line to zero emissions in 2045, as shown in Figure 1, gives us an idea of the average emissions reduction that must occur in each year to achieve the net-negative target. While we saw a temporary drop in emissions with COVID-19 lockdowns and travel restrictions, emissions in 2025 and 2030 are projected to rebound. Figure 2 shows a further breakdown of emissions in the energy sector, which comprise almost 90% of total emissions.

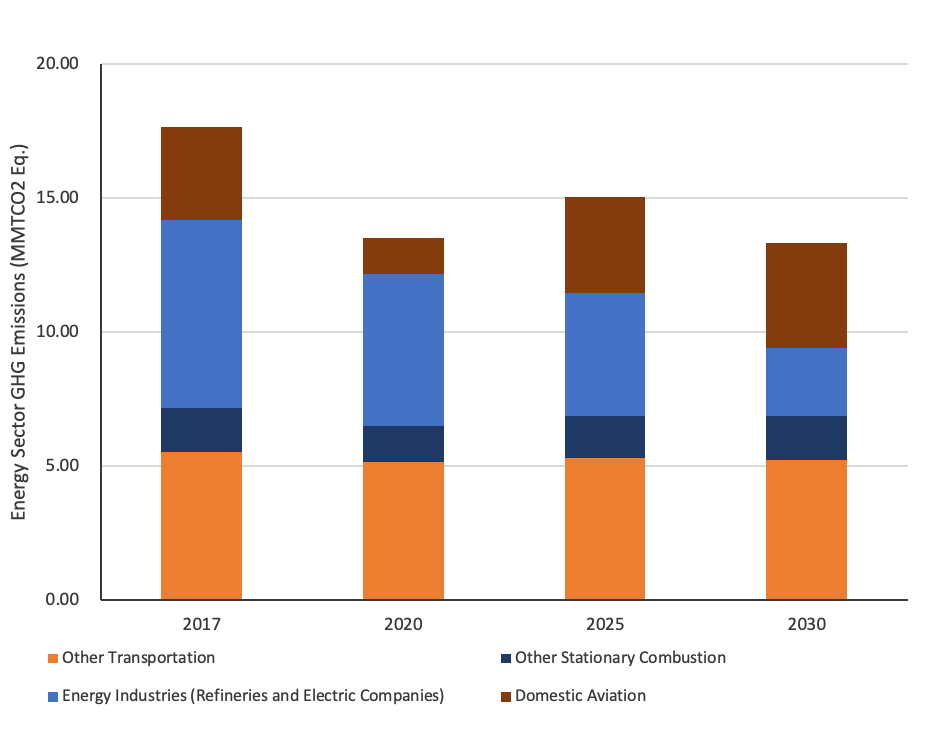

Figure 2. Hawaii GHG Emissions Estimates (2017) and Projections (2020, 2025, 2030) in the Energy Sector

GHG emissions in energy industries, which is predominantly the electric sector, are projected to be more than halved by 2030. This finding is based on the assumption that enough renewable energy generation comes online to meet the State’s RPS target of 40% electricity sales from renewable sources by 2030. However, realization of this goal is not a given, especially considering recent delays in large renewable energy projects due to a wide range of concerns related to land use, habitats and species, and impacts to local communities. These issues will need to be addressed proactively.

Transportation emissions have two major sources, ground transportation (cars and trucks) and aviation, with marine transportation contributing minimally to overall emissions. Contributing to more than half of statewide emissions in 2017, transportation emissions are projected to remain relatively stable through 2030. Ground transportation emissions are projected to see a 7% decline from 2017 levels by 2030. This is largely due to federal regulations that require increases in the average fuel economy of new cars and trucks over time. This modest reduction occurs despite assuming an almost ten-fold increase in electric vehicle travel, going from representing about 1% of total passenger vehicle miles traveled today to about 9% in 2030. Yet, in the absence of significant policy changes and public projects that target people’s overall dependency on cars and trucks, vehicle miles traveled are expected to grow, dampening the overall emissions impact of a more efficient vehicle fleet. And Hawai‘i does not have the ability to set its own vehicle fleet standards, unlike other states like California that have a federal waiver.

For aviation-based GHG emissions, the State’s long-range projection that de facto population will continue to grow – even though we made adjustments to account for the pandemic – means that aviation emissions are projected to increase by over 13% in 2030. Of course, there is a lot of uncertainty in this estimate based on the long-tail of the pandemic, as well as whether new approaches to the visitor industry will take actually take hold.

Unfortunately, our status quo estimates for aviation emissions more than offset what are only modest decline in emissions from ground transportation emissions. This means that carbon sequestration must be an important part of the net-negative goal; however, current inventory and trends show that it is unlikely to be adequate. ICF estimates that carbon sinks are actually on the decline.

All in all, our findings make it hard to conclude that Hawai‘i is “on track” to meeting its important climate goals. Measuring the State’s greenhouse gas emissions has been an important step in realizing what we are up against to stay on track to the 2045 target. It shows us that while goals are important and good, they need to be followed up with implementable policies. In a recent blog post, we discuss how a state-level carbon tax could cost-effectively help to further reduce Hawai‘i’s emissions, and potentially benefit lower income households in this transition. Our recent collaboration with the City and County of Honolulu on O‘ahu’s first Climate Action Plan also shows the important role of municipal actions in reaching the 2045 target. But frankly, getting anywhere close to net negative is not possible without massive federal policy – across the board, but particularly addressing aviation emissions.

Net-negative by 2045 is a good, science-based target. It’ll take actors across the globe to realize this target to avoid the worst predictions of climate change. Achieving decarbonization will require continuous and deep-seated effort at all levels of government, and Hawaiʻi, and everywhere else, has no time to waste when it comes to implementing meaningful policies. After all, falling behind on GHG abatement now means an even greater burden in the future.